The CDC’s High-Impact Prevention strategy takes aim at the stubborn HIV incidence rate in the United States. The only problem: it doesn’t include an ambitious plan for those at risk for the virus

By Jeremiah Johnson

There is no shortage of depressing statistics when it comes to HIV prevention in the United States: 50,000 new HIV infections annually; a 12% increase in new infections among gay and bisexual men and transgender women between 2008 and 2010; an estimated infection rate of nearly 50% among black transgender women; and a projected 50% infection prevalence in gay and bisexual men by the time they’re 50.

For the people who have been most affected by the epidemic, we have failed to make any measurable progress; if anything, the spread of the virus has worsened.

In 2011, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the primary funder of HIV prevention efforts in the United States, redesigned and rebranded its approach with a new strategy called High-Impact Prevention (HIP). Recognizing that funding of U.S. HIV prevention programming is unlikely to see necessary increases anytime soon, the CDC designed this approach to target limited prevention dollars to evidence-based and cost-effective interventions in order to maximize results. The strategy was also meant to reallocate funding to the regions and key populations that are most in need of HIV prevention services.

HIP, however, is more than a redistribution of funds. It is in many ways a retreat from prevention services for HIV-negative individuals. Instead of providing effective options to people at risk for the virus, the strategy focuses largely on the HIV continuum of care—finding individuals who are already living with the virus through testing initiatives and linking them to care and treatment. The aim of this so-called prevention-for-positives approach is to lower the number of new infections by reducing the infectiousness of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA).

Strategies including treatment as prevention (TasP) are essential in any national effort to finally rein in new infection rates in the most affected communities. The landmark HPTN 052 study found that, among heterosexual serodiscordant couples, effective treatment of the HIV-positive partner led to a 96 percent reduction in the risk of HIV transmission. Early data from the PARTNER study presented at the 2014 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) indicate that the benefits of TasP may also extend to gay and bisexual men and transgender women.

Encouraging study findings aside, TasP is not a prevention panacea. The CDC’s lack of focus on HIV-negative individuals represents a tactical misstep and leaves people who are most at risk for acquiring HIV with few effective options. While the HPTN 052 and PARTNER studies certainly establish the preventive benefits of linking PLWHA to treatment, they do not indicate that TasP, by itself, can end the epidemic. Clinical trials in many ways represent a best-case scenario for participants—they may not reflect how such interventions will work in the real world, particularly in the United States, where we have managed to get only around 25 percent of PLWHA to a state of viral suppression.

Many questions remain regarding the rates of viral suppression required to substantially reduce HIV incidence in high-prevalence communities. As summarized in a July 2012 issue of PLoS Medicine by David Wilson of the Kirby Institute of the University of New South Wales, TasP has the greatest potential to succeed in high-income countries. In these settings, HIV epidemics are concentrated, and there is generally universal access to antiretroviral therapy, adequate infrastructure, and guidelines supporting early initiation of treatment. However as Wilson points out, such is the case in Australia and France, and yet incidence—particularly among men who have sex with men (MSM)—has remained flat or is increasing.

Most recently, Andrew Phillips of the University College London and colleagues have explored the community-level impact of TasP within the context of the United Kingdom, where it is estimated that 60 percent of HIV-positive MSM are being effectively treated, yet the epidemic in this population continues to worsen. According to mathematical modeling developed by Phillips’s team and reported at CROI 2014, viral-load suppression would have to reach 90 percent among MSM living with HIV in order to bring the U.K. epidemic under control. Models are, of course, only as good as the assumptions on which they are based, but these findings call into question the ability of TasP to stop an epidemic on its own.

While we try to understand the population-level impact of TasP, there are also individual-level questions to be answered. Is it ethical to essentially deny HIV-negative individuals an opportunity to avoid infection while we gravitate toward an approach that focuses primarily on people already living with HIV? If no new solutions were available in the field of prevention for HIV-negative individuals, we might be able to justify this insular focus on prevention for people who are positive, given the abysmal prevention record of the past decade. This is far from the case, however. The 2010 iPrEX study established the effectiveness of once-daily Truvada as a preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV by demonstrating that, for individuals who took the medication consistently and correctly, the risk of acquiring HIV was reduced by at least 92 percent. At the same time, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) potentially creates a new framework for coordinating the delivery of prevention services—PrEP, as well as mental health care, substance use treatment, sexually transmitted infection (STI) screenings, postexposure prophylaxis, and various ancillary services—through primary care.

To be fair, the CDC has not completely abandoned HIV prevention for HIV-negative individuals. HIP still heralds the virtues of condom distribution; behavioral interventions; and counseling, testing, and referral (CTR) services intended to help keep people negative. But these are the same methods of prevention that have been tried for decades, and, while they have almost certainly had some impact, they have not been enough to stop or even significantly slow the epidemic in key populations.

New evidence seems to show the futility of trying these same interventions over and over again. The 2013 findings of Project AWARE—demonstrating that risk-reduction counseling in conjunction with a rapid HIV test did not significantly affect STI acquisition among STI clinic patients—call into question the effectiveness of CTR and contribute to the growing doubt that behavioral interventions have had any meaningful impact on the epidemic. The CDC itself highlighted the limitations of condoms in a 2013 CROI presentation, which found that intermittent condom use essentially had no statistically significant preventive benefit. Given that in the 2011 National HIV Behavioral Survey 57 percent of MSM indicated that they do not always use condoms, there is growing urgency to try something new.

To end the epidemic on a population level, we cannot rely on TasP alone. At the same time, we cannot limit our focus to traditional methods of HIV prevention to empower those at risk. We must completely rethink HIV prevention and learn to take advantage of every new opportunity for progress that has arisen over the past five years. In 2014, TAG will work with government, academic, and community leaders to go beyond HIP in order to do just that.

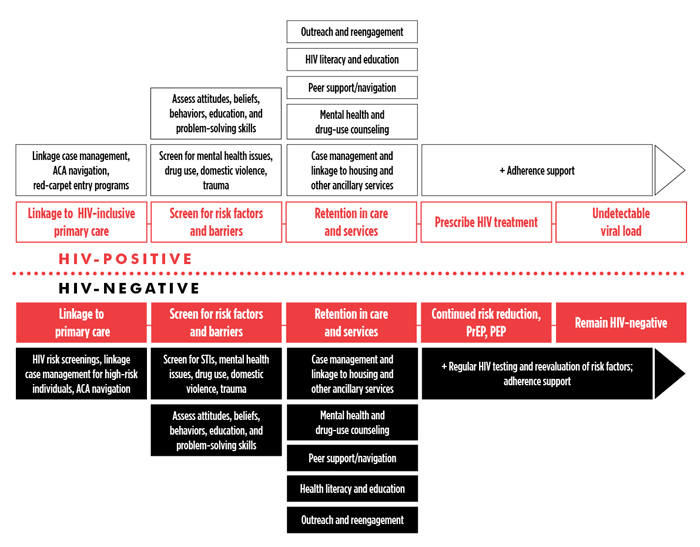

One strategy being developed and explored by TAG is the creation of an HIV prevention continuum, similar to the HIV care continuum model that has already essentially defined key outcomes required for disease management and TasP (see figure).

People struggling to find effective ways to avoid HIV need more than just routine testing, advice, and a fistful of condoms. Individuals at risk for infection need care that is far more comprehensive. Just as treatment and care for PLWHA are considered to be an ongoing process with complex and interconnected parts, prevention for HIV-negative individuals must be understood as a series of related steps that cannot work in isolation. We cannot, in the new ACA era, allow each HIV-negative test to remain an isolated event. Each test is an opportunity to link individuals to health care coverage, provide ongoing and culturally sensitive evaluations of HIV and other disease risk factors, and coordinate medical- and social support services to address barriers to care and evidence-based prevention synergistically.

It is time for us to move on from the siloed interventions housed within HIP to a new kind of holistic prevention approach that helps both HIV-negative and HIV-positive individuals meet their goals in avoiding HIV transmission. By linking heavily affected communities to more comprehensive care, we might even move beyond our singular focus on new HIV infections and work to create general well-being and reduce all-cause morbidity and mortality rates in communities that are often hard hit not only by HIV, but by many other health-related crises as well.•

Figure. A double-helix HIV prevention and care continuum

A work in progress by TAG staff, the above schematic depicts key components of successful engagement in care to achieve critical outcomes required to foster disease-free survival and to ultimately end the HIV/AIDS epidemic. The continuum of care for people living with HIV (top half of the graphic) has been well described and embodies health care delivery and the coordination of essential services to fully support linkage to and retention in care, the commencement of antiretroviral therapy, and maintenance of viral-load suppression. A continuum of care for those who test negative for HIV, particularly those being screened for the virus through AIDS service organization and Department of Health programs, does not exist. Under the Affordable Care Act, testing for HIV should be seen as a critical point of care within the health care system, whereby linkage to affordable health insurance and culturally sensitive care is a priority for those who test negative but potentially remain at risk for the virus. Mirroring the HIV care continuum, an HIV prevention continuum (bottom half of the graphic) details some of the core components of HIV risk reduction and maintained wellness made possible through consistent primary care and the coordination of social support and other ancillary services.