Tax dollars are making it easier for the drug and diagnostics industry to develop and market essential TB products. Is the public getting a fair return on its investment?

By Lindsay McKenna

Motivating the pharmaceutical industry to step up and respond to the burgeoning tuberculosis (TB) epidemic is one thing. Publicly funding its research and development (R&D) only to have it yield prohibitively expensive drugs is something else entirely.

Public-private partnerships, particularly when it comes to diseases that largely affect the world’s poor, are essential. TB has seen only three new drugs developed over the past 40 years. TAG’s 2013 Report on Tuberculosis Research Funding Trends, 2005–2012 cites a US$1.39 billion funding shortfall for TB R&D investment, as well as a 22 percent reduction in private-sector investments. And in the past year alone, both Pfizer and AstraZeneca have pulled out of anti-infectives altogether, despite the recent U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) report, Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2013, which listed multi- and extensively drug-resistant TB (M/XDR-TB) as a “serious threat.”

The problem is that U.S. tax dollars end up supporting the development of private products that, once on the market, are priced out of reach of the populations that would benefit most. Companies also benefit from tax credits, priority review vouchers, and other incentives that potentially far outweigh their minimal R&D investments.

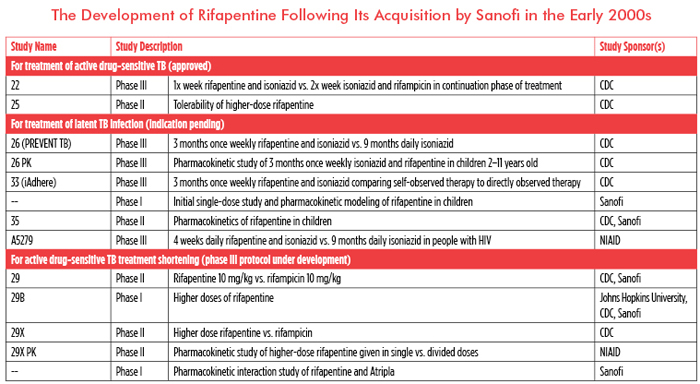

Sanofi’s rifapentine is currently approved for treating active, drug-sensitive TB and shows promise for shortening treatment for both latent and active disease. Yet Sanofi is listed as the primary sponsor of just one of 18 clinical trials of rifapentine documented on clinicaltrials.gov and as a collaborator on only two others. Eleven of 18 trials are sponsored by the taxpayer-funded CDC or the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID).

It would be unfair to say that Sanofi has contributed nothing to rifapentine’s development. In addition to donating money to the CDC Foundation, it is providing study drug to the Tuberculosis Trials Consortium, financing the development of a fixed-dose combination, contributing to the study of rifapentine in children, and looking at potential interactions between rifapentine and Atripla (efavirenz/emtricitabine/tenofovir). While Sanofi does not publicly report its spending on TB research, the average cost of each of the aforementioned studies has been estimated at US$500,000–650,000. These investments, along with US$2 million in donations to the CDC Foundation, bring Sanofi’s financial contribution to a measly US$3.65 million, far from the US$20 million-plus invested by the CDC.

Public dollars overwhelmingly funded the expensive studies critical to rifapentine’s pending approval for the treatment of latent TB infection (see table). The contributions Sanofi has made are valuable in expanding new treatment options to children and people with HIV, but they also broaden the drug’s potential market and profitability, especially as these populations are generally prioritized for the treatment of latent TB infection.

Similarly, AstraZeneca has capitalized on public funding to bring a drug to market without sufficiently matched investments. AstraZeneca’s exit from TB R&D came with a purported commitment to continue developing the novel antibiotic AZD5847; however, the US$10.3 million that AstraZeneca invested in 2012 went primarily to preclinical work unrelated to the development of the drug. While AstraZeneca supported both single- and multiple ascending dose studies for AZD5847—at an estimated US$800,00 and $1.2 million, respectively—NIAID invested twice that in a phase IIa early bactericidal activity trial.

TB drug developers aren’t the only private companies taking advantage of public dollars. Cepheid, the developer of GeneXpert, a fully integrated and automated molecular diagnostic system, received significant public-sector research funds to bring GeneXpert to market and then shirked its moral obligation by pricing the diagnostic technology out of reach for most TB-endemic countries.

Cepheid claims to have invested US$300 million to develop the GeneXpert platform and an additional US$25 million to develop the Xpert MTB/RIF cartridge for TB diagnosis. The U.S. Department of Defense invested US$120 million in the platform’s development, and NIAID and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) invested US$21 and US$9.73 million, respectively, in the TB cartridge’s development. While the amount Cepheid invested in the platform’s development appears far greater than the public investment, Cepheid has also adapted this platform to diagnose a variety of other infections and diseases, allowing it to reap substantial benefits from public-sector investments.

The AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) and the Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics (FIND) were the primary funders of the evaluation studies required for both U. S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval and World Health Organization (WHO) endorsement. The ACTG, funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), invested US$1.4 million in clinical evaluation studies conducted in the United States, and FIND, with funds from the BMGF, invested US$5.63 million in multicountry evaluation studies and demonstration projects.

Even more public money was invested to reduce the price of both the platform and its testing cartridges. The President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) contributed US$3.5 million, and UNITAID and the BMGF put in US$4.1 and US$3.5 million through a 2012 market intervention agreement, which reduced the cost of individual Xpert cartridges by 40 percent. Yet, the price remains unacceptably high, at US$17,000 for the platform and US$10 apiece for the cartridges, and only for a set number of preapproved public-sector purchasers in resource-poor countries, regardless of increased demand and procurement by TB programs.

The TB community has been grateful for even anemic private-sector contributions to R&D and hesitant to demand more accessible pricing, largely out of fear that private-sector companies will abandon TB. Yet private companies are benefiting from publicly funded research, tax credits, and priority review vouchers, while continuously and shamelessly privileging profits over patients.

The NIH actually has legislative power to protect public interests from private companies that fail to make innovations to which public funds have contributed available. In 1980, Congress enacted the Bayh–Dole Act, which includes a clause allowing funding agencies “march-in rights” to reclaim innovations from companies that fail to make them publicly accessible. However, in the 33 years since the Bayh–Dole legislation was passed, only four march-in rights petitions have been seriously considered by the NIH, all of which were later rejected.

The NIH needs to prioritize public interests and start proactively using the legislative power provided by the Bayh–Dole Act to improve access to new tools. Federal funding agencies and the TB community have ignored private-sector abuse of public funds for too long. If we are to achieve zero TB deaths, new infections, suffering, and stigma domestically and abroad, we need to stop the private sector from taking advantage of public funds while ultimately putting profits before patients.•

Correction: April 16, 2014

In the eleventh paragraph of this article, second sentence, the amount contributed by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) should have been US$3.5 million, not US$11.1 million; the latter figure represents the collective contribution of PEPFAR, USAID, UNITAID, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.