Globalizing the insurance model will harm global public health

By Annette Gaudino

In the New York City of the 1850s, firefighting was a private enterprise. Homeowners and landlords purchased insurance plans that included protection from a dedicated fire brigade. When a fire broke out, brigades would arrive on the scene and look for an insurance company seal on the building. No hoses would be turned on until insurance coverage was verified. Often the building would have no seal, as fire insurance was not required. In that case, the rival brigades would fight—at times, rioting—over who would get paid by the insurance company. And while they brawled, the home would keep burning.

In the New York City of the 1850s, firefighting was a private enterprise. Homeowners and landlords purchased insurance plans that included protection from a dedicated fire brigade. When a fire broke out, brigades would arrive on the scene and look for an insurance company seal on the building. No hoses would be turned on until insurance coverage was verified. Often the building would have no seal, as fire insurance was not required. In that case, the rival brigades would fight—at times, rioting—over who would get paid by the insurance company. And while they brawled, the home would keep burning.

Eventually, both the public and the insurance companies realized that everyone would benefit from universal fire protection. If your neighbor’s house is on fire, then you’re also in danger, and every house is vulnerable to destruction. Out-of-control fires also meant heavy financial losses for the insurance industry. In 1865, the New York Fire Department was born, funded by tax dollars and free at the point of delivery. Fire insurance would continue to provide compensation for property loss, but the delivery of life-saving care would be treated as a public good.

The Gangs of New York-era fire brigades are a comically apt metaphor for the current U.S. health care system. Although broadly acknowledged as a defense of a flawed status quo, recent mass mobilizations to stop the repeal of the Affordable Care Act both reflected and contributed to the increasing acceptance in the U.S. political consciousness that health care is a public good and a human right. At the same time, global institutions such as the United Nations (UN) and World Health Organization (WHO) have shifted global health away from the broadly accepted human rights- and care-based framework towards a framework that is based on access to insurance coverage. Although national governments can be held accountable for failing to guarantee the right to health care, the insurance coverage framework recasts health care as a commodity with no legal guarantee of access. This shifts responsibility to individual patients, leaving them to navigate systems armed only with their purchasing power, and presents a significant barrier to care for the approximately 80 percent of people living with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection who live in low- and middle-income countries.

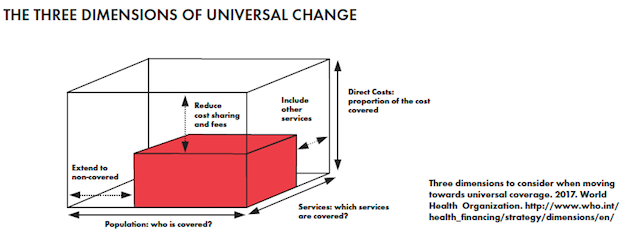

This can be seen most clearly in WHO’s interpretation of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) #3, which ensures healthy lives and promotes well-being for all. This SDG explicitly aims to: “Achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health care services and access to safe, effective, quality, and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all.” In other words, national governments and international donors are called on to protect citizens from the financial destitution that can result from illness, but not from lack of care itself. Universality is stated as a goal, not as the first requirement of any system, enforceable by law. This subtle shift in language has profound implications for the global response to the public challenges posed by infectious diseases, particularly viral hepatitis, HIV, and tuberculosis.

The emphasis on coverage and financial risk protection brings the SDGs up to date—with 19th century concepts of health care rights. The insurance model finances protection by pooling risk—everyone pays into a shared fund and withdraws as needed. The first health benefits offered to workers were social insurance funds, implemented by German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck in the 1880s, that replaced lost wages due to illness. These locally administered funds were run by boards elected by fund members and tended to reflect the higher contributions from workers to these funds: two-thirds from workers versus one-third from employers. These sickness funds established the principle of coverage as something that is owed to workers and a risk that is best shared communally.

But what happens when workers’ rights and the social contract are weakened? The rise of neo-liberal ideology in the late 1970s and early 1980s may be best summed up by Margaret Thatcher’s infamous declaration, “There is no such thing as society. There are individual men and women, and there are families.” She continued: “…there is no such thing as an entitlement unless someone has first met an obligation.” Thus, the employer’s obligation to their workers is erased and replaced with individual responsibility operating in an idealized marketplace, where all things are already equal and the only barriers are deficiencies of character. If there is no such thing as society, then there can be no social contract, and financing for the public good is outside of the acceptable space of public debate. Stigma and discrimination, the twin forces driving infectious diseases, are the natural result of the moral failings of individuals.

The risk-based financing model now takes on another dimension. Instead of offering a shared safety net to catch us when the inevitable facts of life, illness, old age, birth, and death, leave us vulnerable, we must prove our worthiness by avoiding ‘risky’ behaviors. For example, to prove they are worthy of employment and inclusion in an insurance pool, individuals are required to prove, again and again, that they don’t use illicit drugs. Those deemed costly are blamed for rising health costs and individuals are encouraged to believe that each is immune to human frailty. Your house will never burn if you’re careful; illness is only for those who don’t take care of themselves. In a deft reversal of the very concept of insurance, you should never have to pay for someone else’s care. When private profit is added to this system, the pressure to cut costs intensifies, further driving exclusion of the neediest from mechanisms originally designed to share costs and reduce individual burdens.

Indeed, this ideological shift has proven to be deadly in high-income countries, providing intellectual cover for mass government inaction in response to public health crises affecting groups that are considered by nature to be risky and unhealthy: gay and bisexual men, people who use drugs, women, people of color, immigrants, and sex workers. The sick are moral failures and burdens on a so-called general public, conceived precisely to exclude those very groups deemed outside the norm, something for government officials to pray over rather than communities with needs to be met.

In the U.S., rights not explicitly enumerated under the Constitution are not recognized by large segments of the public, including the right to health care. As long as certain social groups are reduced to sets of risky behaviors and the human right to health care remains unrecognized, insurance-based coverage will always incentivize the exclusion of those most in need of care.

Exportation of the insurance model to developing countries, especially at a time of global austerity, institutionalizes the retreat from the social contract at just the moment when investment in infectious diseases could result in the elimination of these global killers. What will be the cost in lives of replacing solidarity and the public good with the logic of the liberal marketplace?

Financing health care on the basis of risk leads to blaming individuals rather than protecting communities. Elimination targets for infectious diseases, including HIV, HCV, and TB, require a public health approach that goes beyond individual risk. By definition, communicable diseases happen between people within communities, and simply cannot be successfully addressed on the level of individual behavior alone. We must continue to advance health care as a human right and public good to achieve global elimination goals.

This goes for domestic elimination goals as well. In the aftermath of the recent all-out Senate and House attacks on the Affordable Care Act and Medicaid, compounded by cruel undermining tactics by the White House administration, it has become abundantly clear that risk-based financing can be profitable or sustainable, but it cannot be both. Although the ACA has lived to see another day and the insurance and health industries are no poorer for it, the U.S. model for universal health care remains a house of cards that continues to fail, especially for the longstanding victims of broken social contracts: the working poor and middle class. As Suraj Madoori lays out in “The Long Game for Health Justice,” the time is ripe to look beyond fragile patchworks of access and coverage and focus instead on publicly funded schemes, particularly single payer.

As wildfires rage across the American West and Europe, we are reminded of our shared vulnerability in the face of nature and our own failure to meet systemic challenges. No house is safe, and entire communities can be devastated unless we act in a concerted fashion to quickly stop and prevent deadly outbreaks. Now is not the time for prayers, ideological experiments, or protecting private industry profits. Only recognition of the universal human right to care can achieve what the moment demands: global investment to heal communities and end infectious disease as a public health threat.