By Cheriko A. Boone, Abraham Johnson, and Richard Jefferys

In a 1989 article by Dr. Anthony Fauci, “AIDS — Challenges to Basic and Clinical Biomedical Research” — which preceded Treatment Action Group’s founding by just a few years — he described NIH/NIAID’s work on establishing the Community Programs for Clinical Research on AIDS, and he called for more minority patients, researchers, and physicians to be engaged in clinical trials of HIV and AIDS therapies. “We envision this as a national program that will broaden the base of our clinical research efforts,” Dr. Fauci wrote, “It is hoped that these research efforts will be innovative and responsive to community needs while also meeting the criteria for sound scientific research.”1 As one of the earliest accounts from a U.S. federal official regarding the need for increasing involvement of racial/ethnic minorities in clinical trials for development of treatments for HIV and AIDS, Dr. Fauci acknowledged two crucial points that for the most part remain true to this day: clinical research on HIV and other diseases must be diverse and representative in recognition of persistent disparities in the most heavily affected groups, and because it’s critical to determine how interventions can be equitably rolled out to different communities.

Despite Dr. Fauci’s pronouncements, it took activism to force the NIH to deliver on that promise. In 1990, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) organized the now famous “Storm the NIH” protest at the agency’s Bethesda headquarters, where some 1000 demonstrators (including TAG Executive Director Mark Harrington) demanded more inclusion of women and people of color in research and more involvement of affected communities at every step of the process. The action became a sort of watershed moment in HIV/AIDS research, which did become more open and inclusive thereafter.

Such laudable examples show that we’ve indeed come a long way in terms of ensuring racial, ethnic, and gender diversity in research since the early days of the HIV epidemic. But we still have a long way to go — and engagement and leadership of marginalized communities is key to getting us there.

In the decades preceding Dr. Fauci’s aforementioned article, the general public reported increasingly positive views toward biomedical science and experimental therapies and rising numbers of privileged Americans were taking part in clinical trials — but participation among racialized and ethnic minorities remained limited.2 One reason was poor outreach: women and people of color were less likely3 to learn about HIV trials in the first place, and early AIDS Clinical Trial Group sites cared for fewer people of color relative to disease burden. Racial disparities have also been partially due to medical mistrust stemming from abuses of Black people and the poor in medical experimentation, demonstrations, and for surgical purposes early in the development of the American healthcare system.4,5 People who use drugs were also excluded from most study protocols, as clinicians worried they’d be unreliable participants.6 These exclusions blunted scientific knowledge about the needs and particularities of key populations. As one researcher put it in 1997, “Failure to include adequate numbers of women and persons of color may limit the generalizability and usefulness of study results for clinical practice.”

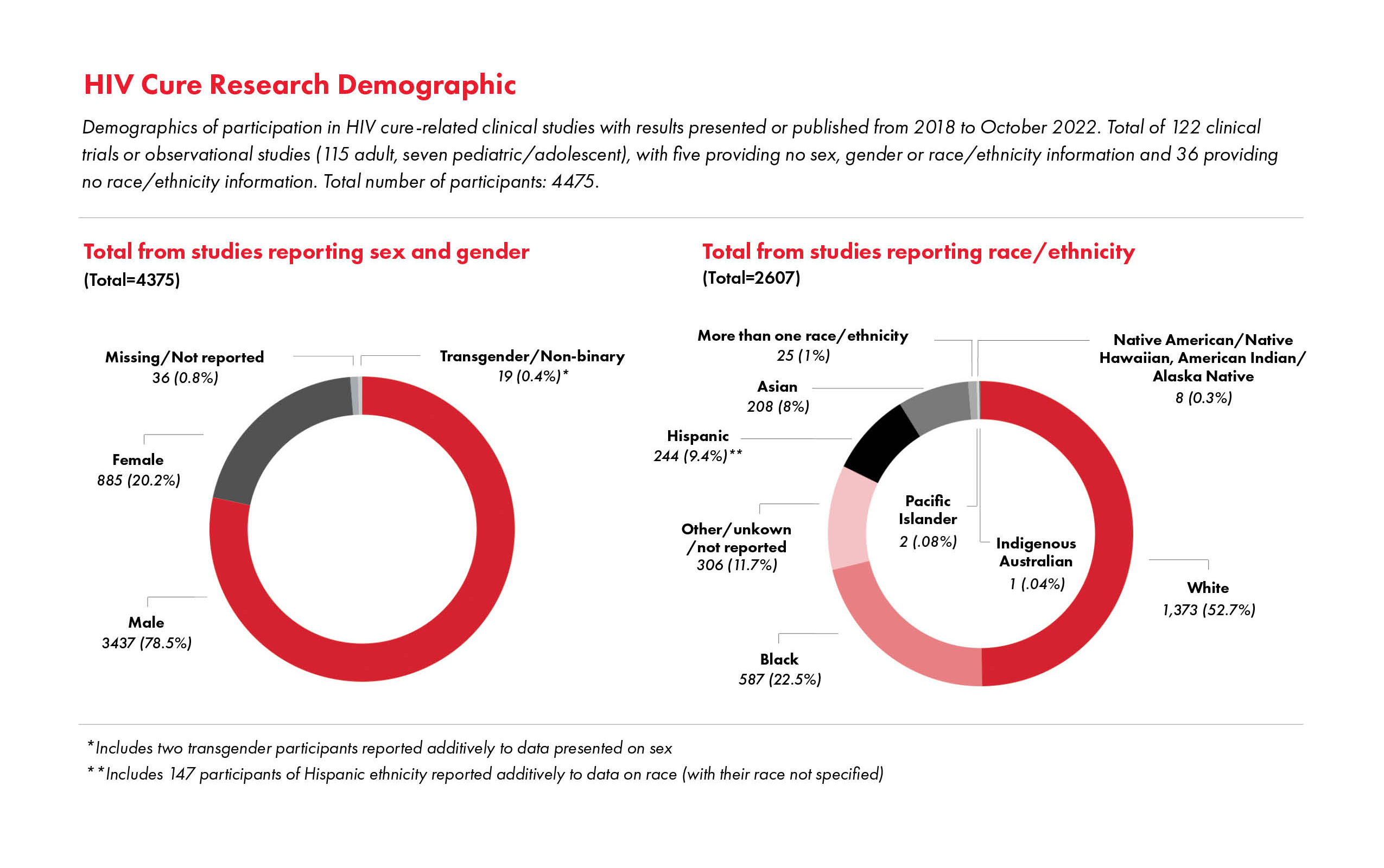

As much as the situation has improved, underrepresentation still presents key points for continued advocacy. For example, underrepresentation of women, including the exclusion of individuals of child-bearing potential, remains a critical issue in HIV biomedical research, such as HIV cure-related research.7,8,9,10 In response to the absence of cisgender women and other individuals assigned female at birth from clinical trials that resulted in approval of emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), TAG lambasted the lack of their inclusion and demanded more research examining the medication’s efficacy for preventing HIV through vaginal exposure.11

Treatment Action Group’s work to advance racial equity in research will be necessary for the foreseeable future. Our work is grounded in the perspective that access to opportunities to participate throughout the research process falls within a Right to Science framework, which emphasizes that such opportunities constitute a human right—not only a right to receive benefits of the applications of scientific progress but also a right to participate in scientific progress.12

Treatment Action Group’s work to advance racial equity in research will be necessary for the foreseeable future. Our work is grounded in the perspective that access to opportunities to participate throughout the research process falls within a Right to Science framework, which emphasizes that such opportunities constitute a human right—not only a right to receive benefits of the applications of scientific progress but also a right to participate in scientific progress.12

Over the years, through partnerships such as the Federal AIDS Policy Partnership’s (FAPP) Research Working Group and collaborations with the HIV Vaccine Trials Network, Black AIDS Institute, and the Southern AIDS Coalition, TAG has advocated for meaningful involvement of persons living with HIV (PLWH) and historically underrepresented groups in the implementation of clinical research studies, as well as translation of science for research advocates. We commend the FDA’s guidance around increasing diversity in clinical trials13,14 and NIH’s commitment to addressing structural racism,15 which includes engagement and career advancement of principal investigators from historically underrepresented groups.

It’s not enough to focus solely on diversity among research study participants. We also need to ensure that meaningful and inclusive community engagement drives all aspects of research endeavors, with intentional investments in maximizing diversity among researchers and clinical staff. There are persistent gaps in this regard that need to be filled. For example, Historical Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) aren’t prioritized enough with respect to NIH funding for HIV biomedical prevention research, despite their reputation as trusted sources for their communities. The U.S South still has the highest incidence of HIV, which unfortunately remains insufficiently reflected in advocacy efforts and funding.

Furthermore, most U.S. investigators in the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) have been of majority race/ ethnicity and sexual orientation.16 To that end, HPTN developed a special initiative, the HPTN Scholars Program, to recruit, engage, train, and mentor young racial/ethnic minority investigators within a large HIV prevention clinical trials collaborative group, which includes support for short-term projects for medical students. Currently, of all the scholars who have completed the program thus far, 22% are Black/African American and 4% are Hispanic/Latino/Latina. It’s essential to increase investments in and scale up such programs in order to reach as many researchers and advocates as possible from underrepresented communities.

Another heartening recent development is the advent of the We the People Research Cohort (WTPRC), a joint project of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Treatment Action Group, Southern AIDS Coalition, and the Black AIDS Institute. This unique partnership developed an innovative curriculum for HIV advocates and trained individuals in research advocacy through a 16-week certification program. The WTPRC project utilizes the framework of Community Based Participatory Research. In development of the training modules and curriculum, we applied Good Participatory Practice Guidelines,17 which involved an iterative process between staff members from partner organizations and community stakeholders. An additional lesson for increasing diversity and inclusion in clinical research comes from the COVID-19 Prevention Trials Network (CoVPN). Clinical research sites that were a part of the CoVPN successfully enrolled 47% of COVID-19 vaccine trial participants who identified as Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC). The increased enrollment of BIPOC in the CoVPN trials further builds the case that equitable enrollment of BIPOC communities is achievable when there are adequate resources and an established commitment to doing so.18

As we look toward achieving the goal of ending HIV, we realize this cannot be done without clear recommendations and policies to ensure that diversity and inclusion is at the center of HIV biomedical prevention research and advocacy. As Dafina Ward, executive director of the Southern AIDS Coalition, poignantly notes: “Ending HIV . . . will require us to lean in and learn from those closest to the epidemic. We need data that tells the whole story — research that captures the full spectrum of experiences and communities impacted by HIV. We have to make things more accessible and remove the mystery around people gaining access to research, resources, and opportunities.”