Winter 2007

Mark Harrington, executive director of the Treatment Action Group, in an opinion published in the Cape Times argues that we are living in a time of potentially great scientific accomplishments … but we are missing the commitment to make those advances a reality.

Last year, in the rural KwaZulu-Natal town of Tugela Ferry, a deadly outbreak of extensively drug-resistant (XDR) tuberculosis made headlines when it ravaged a hospital ward, killing 52 of 53 people infected [all of whom were HIV-positive]. These people died before they could even be diagnosed, let alone treated. Since then, XDR-TB, which is extremely difficult to treat with today’s antibiotics, has been detected in 41 countries and it continues to spread.

This week, for the first time, the world’s largest tuberculosis conference is being held here in South Africa. This is an acknowledgment that urgent action needs to be taken. TB is striking back with a vengeance.

For decades, the world has ignored TB, relying on 40-year-old drugs that take months to cure the disease and an 85-year-old vaccine that does not sufficiently protect beyond childhood. The most common TB diagnostic-the microscope test, introduced in 1882-fails to detect a large percentage of cases and more expensive tests are unavailable in many developing countries.

Neglect, poorly funded TB programmes and lack of quality health services have fueled the emergence of drug-resistant strains of the bacteria. TB is the leading killer of people with HIV, and TB’s deadly interaction with HIV is devastating communities.

Like SARS and avian flu, the uncontrolled spread of drug-resistant TB also poses a potentially devastating threat to global health and economic growth. Only a few months ago, an international panic was created when an American lawyer boarded a plane with what was thought to be XDR-TB.

The spectre of potential nightmare scenarios such as these will grow if XDR-TB is left unchecked.

Yet, despite the XDR-TB threat, a new report released this week shows that, worldwide, government funding for TB research declined last year.

Between 2005 and 2006, funding from governments for TB research fell from $259 million to $244m.

The United States considers drug-resistant TB to be a potent bio-terror threat. Yet last year, the US National Institutes of Health, the world’s largest health research investor and a leader in TB research, cut funding for TB by $8m. Funding from European countries was also stagnant.

The world is failing to keep its promises on TB. Last year, world leaders agreed to adopt the Global Plan to Stop TB: 2006-2015, which made a commitment to increase funding for TB research to $900m a year.

The plan was announced with enthusiasm at the World Economic Forum in Davos, endorsed by the United Nations General Assembly special session on HIV/AIDS in June 2006, embraced by the G8 in July 2006 and ratified by the World Health Assembly in May 2007.

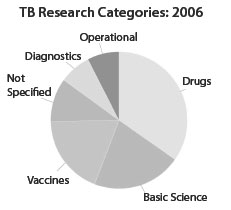

Yet, the year the Global Plan was adopted, the top 40 research donors worldwide spent only $413m on TB research-half a billion dollars less than the Global Plan’s own targets.

If basic science, operational research and a comprehensive research response to XDR-TB are factored in, the Treatment Action Group estimates the total need is closer to $2 billion a year, five times the current amount.

In the short term, there is some good news, mainly from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which increased its support for TB research from $58m to $94m in 2006.

But funding from philanthropies, while filling many current gaps and helping to push a few new products through the pipeline, cannot rescue the world from the lack of sufficient public sector investment, which is responsible for most TB research and development worldwide.

New money is urgently needed to develop new vaccines, drugs and diagnostics to treat TB. With drug-resistant TB emerging, decades of neglect have put us back to square one. It will take many years for new TB vaccines to be proved effective.

We know investing in research can yield lifesaving breakthroughs-like the almost 30 new anti-HIV drugs discovered and brought to market since 1987. Millions of people now benefit from these recent discoveries.

But, unlike HIV, the world has largely ignored TB.

In the long run, the public sector must be willing to pay to expand basic TB science and develop clinical trial infrastructure in order to ensure lasting progress. The private sector must also increase its investment in TB research.

We are living in a time of potentially great scientific accomplishments, but what is missing is commitment to make those advances a reality.

Originally published November 9, 2007 in Cape Times (South Africa).

Tuberculosis Research and Development: A Critical Analysis of Funding Trends, 2005-2006