Reining in prescription drug prices isn’t so much a potential benefit of universal health care, but rather a factor in its affordability and success

By Tim Horn

If there is one thing the majority of Americans agree on, it’s that health care costs—prescription drugs, in particular—are out of control and are significantly contributing to our broken health care system. Despite some campaign trail rhetoric that put the pharmaceutical industry on notice, the White House has yet to announce a bold agenda for curtailing egregious drug pricing. Likewise, Republicans in Congress completely ignored these costs in their cruel and misguided war on the Affordable Care Act and Medicaid, and those on both sides of the aisle in both houses have consistently failed to pass any meaningful price-control legislation.

If there is one thing the majority of Americans agree on, it’s that health care costs—prescription drugs, in particular—are out of control and are significantly contributing to our broken health care system. Despite some campaign trail rhetoric that put the pharmaceutical industry on notice, the White House has yet to announce a bold agenda for curtailing egregious drug pricing. Likewise, Republicans in Congress completely ignored these costs in their cruel and misguided war on the Affordable Care Act and Medicaid, and those on both sides of the aisle in both houses have consistently failed to pass any meaningful price-control legislation.

Actual spending on prescription drugs in the U.S. is controlled by largely secretive and complex systems of negotiations, discounts, rebates, cost-sharing schemes, and assistance programs. They differ considerably from one payer system to another, are based on regulations and statutes that have not kept pace with industry tactics to circumvent these measures, and often yield prices that are still beyond what health care systems and patients can reasonably afford. Can universal health care (UHC) coverage in the U.S. streamline these processes and rein in prescription drug costs, similar to what has been seen in other high-income countries? Possibly, but it will depend on steadfast efforts to dethrone the U.S. as the country with the highest health expenditures in the world (currently $10,000 per capita).

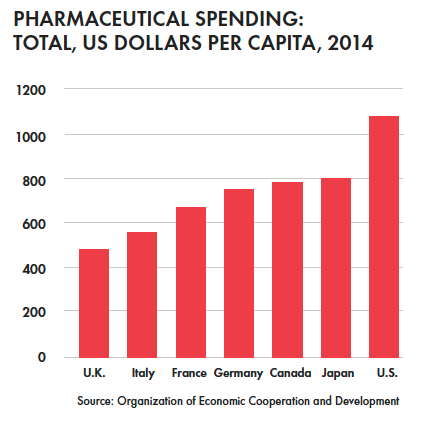

Prescription drug costs in the U.S., relative to overall health spending, are actually the lowest among all G7 countries (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the U.S.). According to the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) data, pharmaceutical spending accounts for 12% of health spending in the U.S., as compared with 17.5% in Canada (second to Japan at 18.8%). However, the U.S. ranks highest in pharmaceutical spending per capita (US$1,081), surpassing second-highest Japan (US$803) and the lowest-ranking United Kingdom (US$481) (see Figure).

Five of the G7 countries ensure UHC, with Japan and the U.S. relying on a patchwork of public and private insurers and an individual mandate. And there are nuances to consider with respect to prescription drug coverage. In Canada—the most frequently cited example of single-payer health coverage—provincial public funds only cover outpatient drugs for the elderly, the very poor, and the very sick. Supplementary private insurance plans and out-of-pocket spending are otherwise required. Canadian health care activists frequently point out that a nationalized scheme to negotiate and cover outpatient prescription drugs is what’s necessary to reduce their costs relative to all health care costs in the country and, ultimately, spending per capita (third highest of G7 countries in 2014 at $786).

A recent study by University of British Columbia and Harvard researchers, published in June 2017 by the Canadian Medical Association Journal, concluded that, among ten high-income UHC counties, per capita spending on six categories of primary care medicines was lowest in countries that were largely dependent on single-payer systems for prescription drug coverage (New Zealand, Australia, Sweden) and highest in countries with mixed (Canada) or multi-payer systems (France, Germany, and the Netherlands). The U.S. wasn’t included in the analysis because it doesn’t ensure UHC and because it “has such exceptionally high pharmaceutical expenditures that its inclusion in the analysis would skew comparisons among the ten more comparable countries studied here.”

The factors that contributed most to reduced expenditures in all of the UHC countries included in the analysis, particularly single-payer countries, were the average mix of low-cost drugs selected in therapeutic categories (choice effects) and differences in the actual prices paid for medicines prescribed (price effects). In essence, countries with centralized—and empowered—systems that can apply a mix of statutory regulations, cost-effectiveness considerations, formula supply contract negotiations, internal and external reference pricing, administrative efficiencies, and voluntary price discounts and patient access schemes are the most likely to control drug costs.

The same will ultimately hold true in the U.S. Guaranteeing health care for all is only half the battle; its affordability will depend on federal and state governments bearing the teeth necessary to rein in high health care costs and prescription drug prices. As TAG fixes its eyes on the former in the wake of the failed ACA repeal and replace efforts, it remains firmly committed to the known successes of the latter.