By Joelle Dountio Ofimboudem

The hepatitis C Virus (HCV) remains one of the deadliest infectious diseases, despite the existence of an effective eight- to-twelve week cure. Still, of the 50 million people estimated to be living with HCV worldwide, 36 percent were diagnosed between 2015 and 2022, and only around 20 percent received treatment. Access to direct acting antivirals (DAAs) must be urgently expanded to save lives. In May of 2023, there appeared to be a promising development on that front: the Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI) and The Hepatitis Fund concluded an agreement with Viatris and Hetero, the leading World Health Organization (WHO)–prequalified generic manufacturers of sofosbuvir (SOF) and daclatasvir (DAC) — the most affordable DAAs that cure HCV within 12 weeks. Under this agreement, Viatris and Hetero committed to reducing the price to $60 Ex Works1 per treatment course in all low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). With these lower prices guaranteed, DAAs finally seemed within reach for people who need them most.

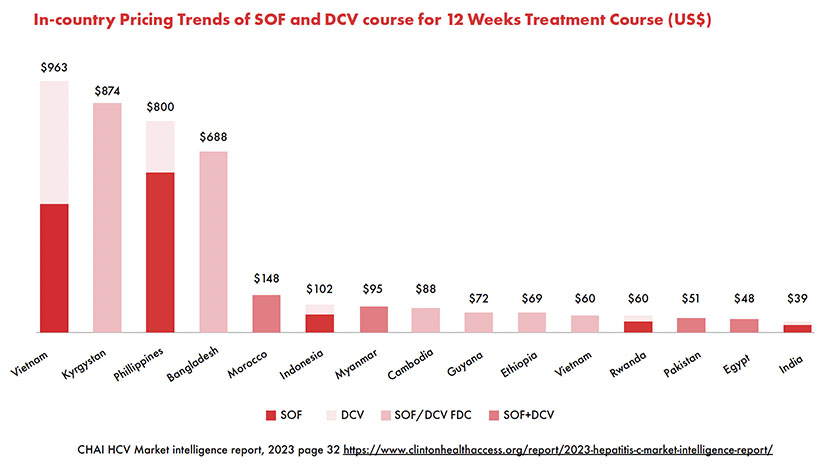

However, more than a year later, the agreement’s impact appears limited: most LMICs continue to pay exorbitant prices for DAAs. People with HCV in Vietnam, for example, pay nearly $1000 for SOF/DAC,2 and people in the Philippines and Kyrgyzstan pay $800 and $874, respectively.3

Despite a clear desire on behalf of CHAI, the Hepatitis Fund, and the generic manufacturers to ensure that people with HCV access curative treatments to meet the WHO viral hepatitis elimination goals, the fact that the lower negotiated prices have yet to become a reality on the ground demonstrates the limitations of such piecemeal agreements with drug manufacturers to address the high cost of essential medicines. In addition to science and such upstream stakeholder deals, policy and activism are the necessary cornerstones for access to health technologies globally. To capitalize on the promise of $60 for DAAs, national health programs must scale up diagnostics and coordinate pooled procurement mechanisms. Civil society and affected communities also have a key role to play in realizing the benefits of lower prices for HCV cures.

Why DAAs Remain Inaccessible Despite the Lower Prices

According to CHAI, since the deal’s announcement in May 2023, countries have simply not taken up the opportunity

- in fact, interest has been so minimal that the participating generics manufacturers are reportedly considering pulling out of the Given the global prevalence of HCV and the high cost of treatment in most countries, this is very telling.

There are many possible reasons for governments’ inaction on cheaper DAAs, such as:

- The COVID-19 pandemic casued health systems to forego other national health priorities in favor of a pandemic response, and this has not changed post-pandemic.

- Lack of routine medical care and the complicated HCV diagnostic process mean people have few opportunities to get screened and tested, so people living with HCV may only present to health facilities once they already have symptoms of serious liver damage.

- Political leaders and national health programs pay little attention to HCV (and viral hepatitis in general) and do very little to raise awareness about it, so there’s no commercial demand for DAAs.

- As one HCV drug manufacturer explained in an email, “[There is a] lack of proper/timely demand Ad hoc requests can no longer sustain this regimen … This situation is causing critical issues to the manufacturer community because Raw Material planning goes haywire … maintaining a manufacturing site with minimum and recurrent overheads, ensuring decent number of registrations across regions and not getting enough business is not a great situation for any manufacturer.”4

- Drug procurement policies in LMICs often operate in a nontransparent manner without engaging advocates or civil society, and officials may not be aware of the $60

- Some country-level barriers to generic DAAs: in South Africa, for instance, the National Medicines Regulatory Authorities has failed to utilize the WHO Accelerated Registration process to collaborate with the WHO in the approval of generic DAC, making it impossible for generic DAC to be available in the country.5

Taken altogether, it shouldn’t be surprising that negotiated price reductions — even if coupled with effective procurement strategies — may not result in getting cures to everyone, everywhere who need them. What we need today is a dedicated movement for global health equity more broadly and national or regional campaigns for viral hepatitis elimination that directly and strategically target and question the inequities in national and global health and international trade, as well as intellectual property — established by the World Trade Organization Trade and Related aspects of Intellectual Property Rights Agreement — such as the Médecins Sans Frontiers Access Campaign (MSF AC) launched in 1999.6

The imminent closure of the MSF AC demands renewed civil society commitment to addressing the failure of the market- driven model of pharmaceutical research and development to deliver safe, affordable, and effective medicines for millions of people across the world in a timely manner. Advocates must build institutional capacity to fill the vacuum left by MSF AC, including through trainings, and community engagement, on the real barriers to access to medicines at the international, regional, and national levels among communities and civil society to enable people to understand why it is critical to mobilize and demand access to medicines. This approach, which was used by the MSF AC, allows for continuity; movement and network building across countries, regions, and globally; and knowledge exchange, enabling civil society to identify stakeholders within their communities and countries for targeted advocacy and to take action to ensure broader outcomes.

Now more than ever before, health advocates need to mobilize to build a global movement for viral hepatitis elimination to meet the 2030 viral hepatitis elimination goals. Generating grassroots activism toward HCV elimination, as we have seen in HIV and tuberculosis, is a challenge, but it is both possible and urgently necessary. HCV elimination advocates will have their work cut out for them and must mobilize virtually and across borders to pursue a multipronged strategy to achieve a variety of demands, including:

- Pushing for the implementation of national HCV elimination plans, or the development of similar plan in countries that don’t yet have them, and political leadership in HCV

- Engaging officials and the public on HCV awareness using culturally appropriate messaging for key populations before generics manufacturers pull out of the initiative.

- Leveraging existing donor funding programs and infrastructure such as PEPFAR and Global Fund to push for the integration of HCV testing, treatment and harm reduction services within these programs at the national level, and continuously making the case for the need to fund HCV and viral hepatitis elimination.

- Proposing and pushing for a coordinated and transparent pooled procurement system to achieve economies of

- Emphasizing that there is an estimated return on investment of US$2–3 for every dollar invested to prevent liver cancer deaths and increased costs of cancer treatment and care in the future, and that failing to scale up viral hepatitis diagnosis and treatment by 2030 will drive an additional 9.5 million new cases of viral hepatitis, 2.1 million cancer cases, and 2.8 million additional deaths.

- Greater integration of HCV services into primary care and nonhealthcare settings, and expanding access to point-of-care testing to connect more people to care and limit loss to follow-up.

- Improve data and categorization of deaths driven by HCV for a more accurate and holistic picture of the virus’ toll.

Finally, an effective movement to end HCV must center the social realities of communities most affected by HCV; namely, people who inject drugs, people experiencing poverty and homelessness, incarcerated populations, men who have sex with men, and more. Harm reduction and prioritizing people with HIV are key to finding and treating more people with HCV. Scaling up harm reduction services to ensure broader access to these services and safe injection use, equipping harm reduction centers to provide universal HCV screening alongside point-of-care HCV RNA testing to all people who inject drugs and ensuring coordinated and timely treatment initiation would enable many countries to regain the trajectory to HCV elimination by 2030. The considerable societal barriers these vulnerable communities face in accessing basic needs and social supports are directly related to governments’ indifference toward HCV — as history shows us, movements to combat these oppressions are key to efforts to protect public health.

Endnotes

1. This is an international trade term that describes when a seller makes the goods available to the buyer at a specific location (usually the seller’s warehouse or dock) and the buyer must cover all transport arrangements and costs. Ex Works pricing only encompasses the cost of producing a product. When the price of a good is set Ex Works, the buyer is responsible for other risks, such as loading them onto trucks, transferring them to a ship or plane, transport, export documentation, all freight charges, meeting customs regulations, and fulfilling the importation and delivery process.

2. Clinton Health Action Initiative. HCV market intelligence report 2023 [Internet]. https://www.clintonhealthaccess.org/report/2023-hepatitis-c-market- intelligence-report/ p 34. [Cited 2024 September 25].

3. World Health Organization. Global hepatitis report 2024: action for access in low- and middle-income countries. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240091672 p 69.[Cited 2024 September 25].

4. Generic HCV drug manufacturer personal communication with: Joelle Dountio Ofimboudem (Treatment Action Group, New York, NY) 2023 July 11.

5. TAG. Lost in translation. TAGline 2023. New York: Treatment Action Group [Internet]. https://www.treatmentactiongroup.org/wp-content/ uploads/2023/10/oct_2023_tagline_final.pdf [Cited 2024 July 31].

6. MSF. What we as a civil society movement demand is change, not charity [Internet]. https://msfaccess.org/about-us [Cited 2024 September 25].