By De’Ashia Lee

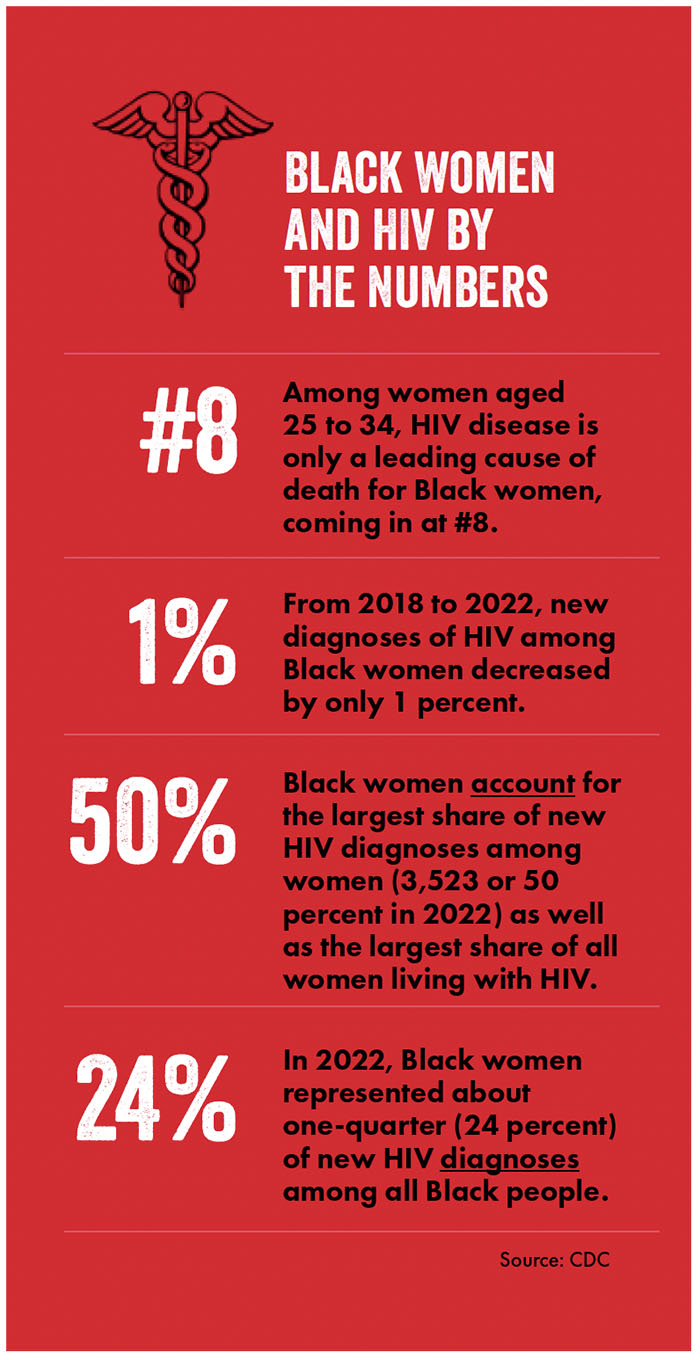

Among women aged 24–35, Black women were the only U.S. demographic for which HIV disease was a leading cause of death in 2021. 1 This alarming health disparity is the end result of a culture of oppression and devaluation of Black women that has persisted since slavery. Throughout history, Black female bodies have been exploited and stigmatized in the name of scientific and medical advancement. From the invasive gynecological experiments on enslaved women by J. Marion Sims to the utilization of Henrietta Lacks’s cells without her consent, Black women have been pivotal yet involuntary contributors to key medical breakthroughs. This history of exploitation has contributed to significant and ongoing health disparities, with Black women experiencing high HIV and maternal mortality today.

Black women face systemic barriers to accessing quality healthcare, including biases within the medical community. Their mistrust of the healthcare system, especially as it relates to reproductive and sexual health, emerges from these biases, which are deeply rooted in historical exploitation. Historically, when Black women have engaged with sexual and reproductive healthcare, they have experienced an institution that devalues their right to reproductive justice and informed consent. Black women have been tortured to perfect surgical procedures, went untreated for syphilis, were unknowingly sterilized, and have had their genetic material stolen and used to achieve some of the greatest medical advances known to humanity — without attribution or financial compensation.

Anti-Black racism and sexism, which concurrently impact Black women, are as woven into healthcare as the two snakes are woven into the caduceus of the healthcare crest. J. Marion Sims is often considered the “Father of Gynecology” for his work on discovering a surgical cure for vesicovaginal fistula, a complication of childbirth that causes the vagina to continuously leak urine. Sims perfected this surgical technique by operating on nonconsenting, enslaved African cisgender women — without anesthesia. Many of these women underwent repeated, torturous procedures, with some having as many as thirty operations.2 The disregard for Black women’s consent and the belief that Black women have a higher threshold for pain are examples of the historical artifacts of anti-Black racism that are foundational to the healthcare institution we know today.

The historical lack of consent experienced by enslaved African cisgender women is an injustice that still reverberates through generations today, manifesting in a lack of bodily autonomy that has been ingrained over centuries. This has had lasting effects on Black women’s health, contributing to the sexual health disparities they experience currently, such as Black women being the only female demographic for whom HIV disease is a top ten leading cause of death3 and HIV criminalization laws targeting sex work, which disproportionately impacts Black women.4 The U.S. Public Health Service (USPHA) Untreated Syphillis Study at Tuskegee is another glaring example of the exploitation of Black bodies and the complete disregard for the sexual health of Black women. In the Tuskegee Study, Black men were left untreated and uninformed about syphilis so doctors could study the natural progression of an untreated syphilis infection. The wives and female partners of these men were ignored, unknowingly unprotected and untreated, and often gave birth to children with congenital syphilis.5 The lack of consideration for the reproductive health of these women speaks to a persistent devaluation of Black women’s bodies.

A woman’s right to make decisions for her body is a reproductive justice that has never truly included Black women. The sterilization of Black and other women of color was a state-sanctioned medical procedure that disproportionately targeted marginalized women in the twentieth century. It was so common in the South that it was colloquially referred to as a “Mississippi Appendectomy,” a term coined by activist Fannie Lou Hamer, who in 1961, was sterilized without consent after seeking treatment to remove a uterine tumor. From 1950 to 1966, Black women in North Carolina were sterilized at more than three times the rate of white women, many without their consent.6

One of the most notable cases of informed consent violations involves a Black woman named Henrietta Lacks. Lacks sought treatment for cervical cancer at John Hopkins University in 1951. She died from the disease, but not before doctors took and shared samples of her tissues without consent. Her cells, which have the unique ability to survive and reproduce, have led to dozens of scientific and medical breakthroughs. Despite the immense scientific advancements made with her genetic material, it wasn’t until 2023, more than seventy years later, that Henrietta Lacks’s descendants reached a settlement with Thermo Fisher Scientific for the use of HeLa cells,7 highlighting a systemic culture in which Black women are expected to contribute to the greater good without proper acknowledgment

While modern reproductive justice movements advocate for the right to access healthcare and make decisions about their own bodies, Black women have historically been excluded from reproductive justice, facing significant injustices in medical disciplines related to reproductive or sexual health care. These fields, which include sexual, gynecological, and obstetric health, have often failed to provide Black women with the safety, respect, and care they deserve. Many enslaved African women relied on their knowledge of herbs to terminate pregnancies as an act of resistance and to reclaim control of their bodies. They did not trust a system that was built and operating on the exploitation of their bodies and their pain to care about their mental, physical, or emotional well-being. This is evident today in America, where it is dangerous for a Black woman to give birth. In 2021, Black women had the highest maternal mortality rate in the United States, almost three times the rate of white women, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention.8 Amid this alarming statistic is the unaddressed anti-Black racism in healthcare, a legacy that traces back to J. Marion Sims, who intentionally taught students to minimize and ignore Black women’s pain. The tendency among healthcare professionals to dismiss Black women’s symptoms is rooted in historical injustices and attitudes and perpetuates systemic bias in healthcare, resulting in the health disparities we see today.

Another example of a health disparity that persists today is the lack of priority given to Black women’s health in research. Much like the Tuskegee Study, which ignored the wives and female sexual partners of the Black men involved, many contemporary research studies also exclude Black cisgender women, focusing solely on men and transgender women. This exclusion has significant consequences given the higher rates of HIV morbidity and death in Black women. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), a new kind of preventive medication first released in 2012 to prevent sexual transmission of HIV, is an example of this disparity. In the early iterations of PrEP studies, Black ciswomen were largely excluded despite the clear data highlighting the need in this demographic. As we saw in the Tuskegee Study, males are engaged by the scientific community and the healthcare system and females — who are capable of both sexual and perinatal transmissions — are largely ignored and unstudied.

The lack of consent and bodily autonomy exists in HIV care and services and often manifests as limitations imposed on women, such as dissuading women living with HIV from breastfeeding due to concerns over transmission. These restrictions affect Black women and contribute to existing health inequities. Achieving health equity for Black women requires systemic changes, such as respecting bodily autonomy, promoting informed consent, and expanding clinical trial inclusion and access to innovative medications for HIV prevention and treatment. A step in the right direction would be universal access to the newest HIV prevention modalities, which have proven more effective than oral PrEP, as shown by the Gilead PURPOSE 19 and PURPOSE 2 studies, which found lenacapavir, a twice-yearly injectable antiretroviral agent, 100 percent effective in preventing HIV in cisgender women and 96 percent effective in cisgender men, transgender men, transgender women, and gender non-binary individuals.10 If global and national partners work together to secure universal access at affordable prices to the most effective, evidence-based HIV prevention and treatment interventions, and with more research and integration of women’s perspectives, these scientific achievements can help close gaps in HIV prevention and care for Black women, ensuring more autonomy and better health outcomes.

Endnotes

- Curtin SC, Tejada-Vera B, Bastian BA. Deaths: leading causes for 2021. Natl Vital Stat 2024 Apr 8;73(4):69.

- Wall The medical ethics of Dr J Marion Sims: a fresh look at the historical record. J Med Ethics. 2006 Jun;32(6):346-50.

- Paz-Bailey G, Heffelfinger JD, Charles V, et al. Prevalence of HIV among U.S. female sex workers: systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2016 Aug;20(8):2318-32.

- Gamble VN. The Tuskegee Syphilis Study and women’s health. J Am Med Womens Assoc (1972). 1997 Fall;52(4):195-6.

- Salas A brief history of sterilization abuse in the U.S. and its connection to alleged ICE mass hysterectomies in Georgia. National Women’s Health Network [Internet]. 2020 October 2. https://nwhn.org/a-brief-history-of-sterilization- abuse-in-the-u-s-and-its-connection-to-ice-mass-hysterectomies-in-georgia/.

- Skene L, Brumfield S. Henrietta Lacks’ family settles lawsuit with a biotech company that used her cells without consent. AP News [Internet]. 2023 August 1. https://apnews.com/article/henrietta-lacks-hela-cells-thermo-fisher-scientific- bfba4a6c10396efa34c9b79a544f0729 [Cited 2024 August 5].

- Stafford K. Why do so many Black women die in pregnancy? One reason: Doctors don’t take them seriously. AP News [Internet]. 2023 May 23. https://projects.apnews.com/features/2023/from-birth-to-death/black- women-maternal-mortality-rate.html. [Cited 2024 August 5].

- Hoyert DL. Maternal mortality rates in the United States, 2021. NCHS Health E-Stats. 2023.DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:124678

- Bekker LG, Das M, Abdool Karim Q, Ahmed K, Batting J, Brumskine W, et al. Twice-yearly lenacapavir or daily F/TAF for HIV prevention in cisgender N Engl J Med. 2024 Jul 24.

- Kelly CF, Acevedo-Quiñones M, Agwu AL, et al. Twice-yearly lenacapavir for HIV prevention in cisgender gay men, transgender, and gender-diverse people: Interim analysis result from the PURPOSE 2 study (Abstract 0208). Paper presented at: HIVR4P 2024; 2024 October 6-10; Lima, Peru. https://presentations.gilead.com/files/6917/2839/9459/Kelley pdf