Interview questions and editing by Erica Lessem, Bryn Gay, Joelle Dountio Ofimboudem, Annette Gaudino, and Elizabeth Lovinger

The World Health Organization set ambitious targets for eliminating the hepatitis C virus (HCV) among the 58 million people living with the disease, but most countries are far from reaching them. How could long-acting technologies, which extend the release of a drug over a period of time, such as over weeks or months, accelerate reaching these targets, especially in low- and middle-income countries, where most people living with HCV reside?

The World Health Organization set ambitious targets for eliminating the hepatitis C virus (HCV) among the 58 million people living with the disease, but most countries are far from reaching them. How could long-acting technologies, which extend the release of a drug over a period of time, such as over weeks or months, accelerate reaching these targets, especially in low- and middle-income countries, where most people living with HCV reside?

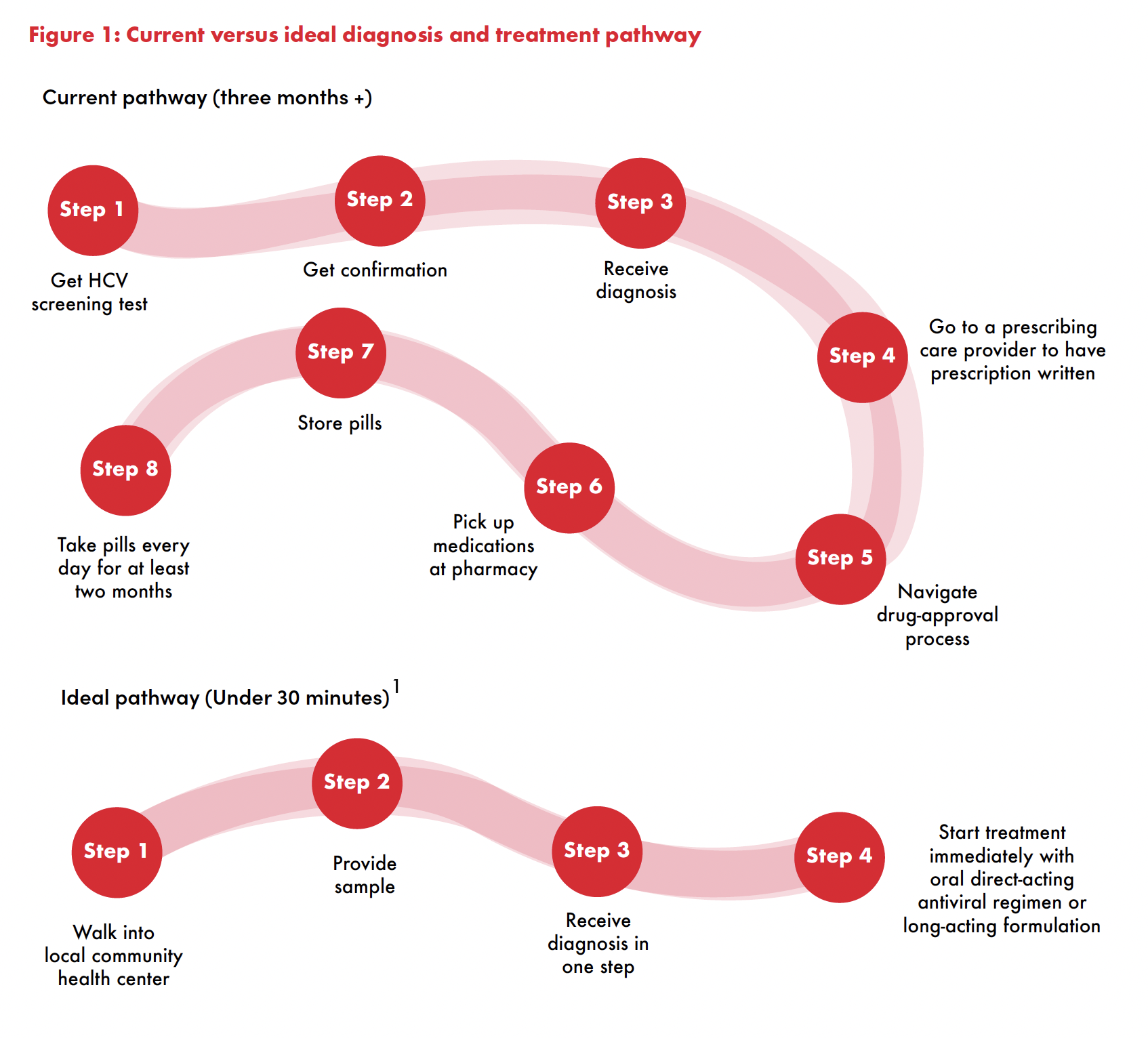

The current all-oral treatment regimen is safe, tolerable, and effectively cures HCV in over 95 percent of people when they also have access to diagnostics and linked to care. The current pathway to diagnosis and starting treatment still has many steps, and establishing the required infrastructure demands sustained financing, health trainings, political leadership, and an enabling policy environment (see Figure 1). Creating that infrastructure for HIV took almost ten years and billions of dollars with the support of the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief and Global Fund. A long-acting treatment that can cure in one health visit could couple point-of-care testing for HCV (which already exists) with immediate treatment initiation. Public health programs could deploy it in settings where there is no permanent infrastructure for medical care, pharmacies, or even a home where the medications can be stored.

Are there health systems capacity issues that need to be addressed in the drug development itself to ensure broad access in low- and middle-income countries?

Some long-acting technologies require cold storage or mixing on-site, and there are concerns that would add layers of cost, training, time, and quality assurance. In my view, developing a long-acting HCV cure that does not have those requirements is ideal but not necessary. My sense is that a public health campaign approach could still manage that type of preparation. Imagine an HCV elimination van that moves around and offers free testing and cure. Those on the van can certainly be trained to prepare the formulation.

You have started to survey providers and patients about their preferences when it comes to different formulations. Could you share anything from your findings so far?

Our findings have not yet been published. However, in general, we find that there is high acceptability for long-acting treatments — highest for injections, and highest when someone already has experience with that form (for example, already had an implant once). That said, there are some who prefer pills and a small fraction who really hate getting injections. In those respects, persons who inject drugs are similar to other persons living with HCV. Long-acting treatments are particularly advantageous for persons who might not have stable housing that provides a place to store medications. We also are aware of research that shows you can safely hand out an entire HCV treatment course of pills.2 So taken together, we believe in a model where both are offered.

You have done extensive work on HCV treatment and care in prisons in Louisiana. How would long-acting HCV cure work in a detention setting?

A long-acting HCV treatment would be ideal for carceral settings. Incarcerated people frequently are moved around within and between facilities, which poses interruptions to longer courses of treatment. Frequent medical care also requires transporting incarcerated people to get treatment, which is a lot of work and cost for the system. A one-time test and cure approach is preferable.

Unitaid’s LONGEVITY project is supporting the development of a long-acting formulation of glecaprevir and pibrentasvir (G/P). What are the challenges with developing long-acting formulations of drugs, and how did this drug combination become the frontrunner for a long-acting formulation?

Unitaid’s LONGEVITY project is supporting the development of a long-acting formulation of glecaprevir and pibrentasvir (G/P). What are the challenges with developing long-acting formulations of drugs, and how did this drug combination become the frontrunner for a long-acting formulation?

I am new to this and have learned a lot from the pharmacologists and chemists on our team. In short, properties that make a drug great for oral use (water-soluble and fast uptake into the liver from the gut) are the opposite of what is ideal for a long-acting injection. That is particularly true for sofosbuvir. The rapid uptake of sofosbuvir from the gut into the liver contributes to its efficacy as a pill but makes it harder to formulate as a long-acting treatment. Also, with pills, one can overcome lower potency by ingesting more, while with injections, the amount that can be injected is limited. The release of a medicine must be chemically managed instead of just taking the pills at a certain frequency. It is much harder. Other helpful properties of G/P include not inducing hypersensitivity allergic reactions (so that oral test doses aren’t needed), working for all HCV genotypes, and being the shortest approved therapy (eight weeks).

If the LONGEVITY project successfully develops long-acting formulations of HCV for treatment, what’s next? Is there potential for long-acting prevention of HCV, similar to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV or tuberculosis preventive therapy?

I do not envision medical PrEP for HCV. One simple reason is that no one has received these medications for more than 3–6 months, so we don’t have any sense of the safety. Also, HCV can be cured. So, in my view, it just makes a lot more sense to have a program that rapidly tests and cures — along with harm reduction — versus trying to develop PrEP for HCV.

But there is certainly more to do after developing the product. We need to engage with those who can use it, ideally before approval. I like the example of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). It was absolutely crucial to engage the community and potential recipients to develop a formulation that matches what women in sub-Saharan Africa needed. We certainly have to do that for HCV as well. We also need to consider the other stakeholders. For example, ministries of health and carceral medical facilities need to be convinced of the potential and prepare teams to deploy the treatments.

Sir Houghton, one of the Nobel Prize recipients for discovering HCV, says an HCV vaccine could be ready in five years,3 roughly along the timeline of the LONGEVITY project. How would a long-acting treatment formulation complement a vaccine?

Michael is super smart and a terribly thoughtful person who has been working on a vaccine since early 1990s. Developing a vaccine is great but doesn’t help the 58 million people who already have HCV.

*Dr. David Thomas is Professor of Medicine and Director of the Division of Infectious Diseases at Johns Hopkins Medicine. He is Principal Investigator of the Johns Hopkins project for developing long-acting technology for HCV and the lead investigator on HCV clinical development under the Unitaid LONGEVITY grant.

Endnotes

1 Applegate TL, Fajardo E, Sacks JA. Hepatitis C Virus Diagnosis and the Holy Grail. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2018 Jun;32(2):425-445. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2018.02.010.

2 Solomon SS, Wagner-Cardoso S, Smeaton LM, et al. A simple and safe approach to HCV treatment: findings from the A5360 (MINMON) trial (Abstract 135). Paper presented at: CROI 2021. Conference of Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 2021 Jun-Nov 3; Virtual.

3 Downey K Jr. Hepatitis C vaccine could be ready in 5 years, Nobel Prize winner says. Healio [Internet]. 2021 July 26 [cited Sept 6]. https://www.healio.com/news/primary-care/20210726/hepatitis-c-vaccine-could-be-ready-in-5-years-nobel-prize-winner-says