By Joelle Dountio Ofimboudem and Sara Helena Gaspar

Background

Intellectual property is a major barrier to access to medicines worldwide because it creates corporate monopolies that restrict supply, keep prices high, and prevent people from accessing innovative health products. However, in the context of hepatitis C virus (HCV), intellectual property is no longer the major barrier to treatment access in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) included in voluntary licenses. In these licenses, originator drug manufacturers of the most-commonly used pangenotypic direct acting antivirals (DAAs) that cure HCV — sofosbuvir (SOF) and daclatasvir (DAC) combination — have authorized generic manufacturers to manufacture and commercialize generic versions of the DAAs in some LMICs at lower prices. Yet these DAAs still aren’t reaching most of the people who need them in many of these countries. Globally, only about 21 percent of the estimated 58 million people living with HCV know their status, and four hundred thousand people continue to die of HCV-related causes each year.

Following pressure from health advocates and activists denouncing the high cost of life-changing DAAs that cure HCV, Gilead (the manufacturer of SOF sold under the commercial name Sovaldi®) granted voluntary licenses to seven Indian- based generic manufacturers in 2014, making it possible for the latter to manufacture and commercialize generic SOF and velpatasvir for 91 developing countries. Similarly, Bristol- Myers Squibb (the manufacturer of Daclatasvir sold under the commercial name Daklinza®) granted a voluntary license for Daklinza® to the Medicines Patent Pool (MPP) in 2015, allowing MPP to grant sublicenses to generic manufacturers. Five years later in 2020, Bristol withdrew marketing authorizations for DAC, allowing its patents to lapse. As of 2023, about six generic pharmaceutical companies have received World Health Organization (WHO) prequalification status1 to manufacture and commercialize generic SOF and DAC.

Now that Viatris and Hetero, two of the leading WHO- prequalified generic DAA manufacturers, have pledged to reduce the cost of the full HCV treatment course to $60 to meet the 2030 HCV elimination goals, there is an urgent need for health advocates to identify and raise awareness about the current barriers to HCV care and mobilize to engage with policymakers and other stakeholders to address them and ensure everyone with HCV has access to the cure.

Non-Intellectual Property Barriers to HCV Care

1. Non-Registration of Originator Drugs and Failure of National Medicines Regulatory Authorities to Utilize Available Options for Drug Approval

Before a pharmaceutical product can be introduced into any country’s market, its manufacturer must obtain market authorization from the national medicines regulatory authority (NMRA). Generic manufacturers are required by NMRAs to demonstrate the equivalence of generic drugs to the originator drug in order to obtain market approval. To demonstrate equivalence, generic manufacturers conduct bioequivalence studies according to specified guidelines comparing the generic (test) and the originator product.

When a generic manufacturer of a medicine that is WHO- prequalified seeks market approval in a country where the originator did not submit the dossier for market approval, the NMRA can use the WHO Accelerated Registration process to collaborate with the WHO in examining the dossier. In the case of DAC, for example, Bristol did not register Daklinza® in South Africa before leaving the HCV market, and the country’s NMRA — the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA) — requires that originator drugs must be registered before generic versions can be approved. An alternative approach for SAHPRA would be to use the WHO Accelerated Registration process to collaborate with the WHO to register generic DAC. Because SAHPRA has not used this approach, generic DAC cannot be introduced into the country. Hence, only originator pangenotypic DAA combinations developed by Gilead are available on the national market at between $1,000 and $1,500 for a full treatment course, which is unaffordable for most people with HCV and for the public health program.

To address this, NMRAs in countries where the lack of registration of Daklinza® hinders the registration of generic DAC should use the WHO collaborative registration process to promote competition and price reduction in the DAA market. In addition, given that Gilead’s voluntary license covers another pangenotypic DAA, sofosbuvir/velpatasvir, policymakers in LMICs included in the voluntary licenses need to leverage these opportunities to ensure that more than one pangenotypic DAA combination is available on the domestic market to promote generic competition and price reduction.

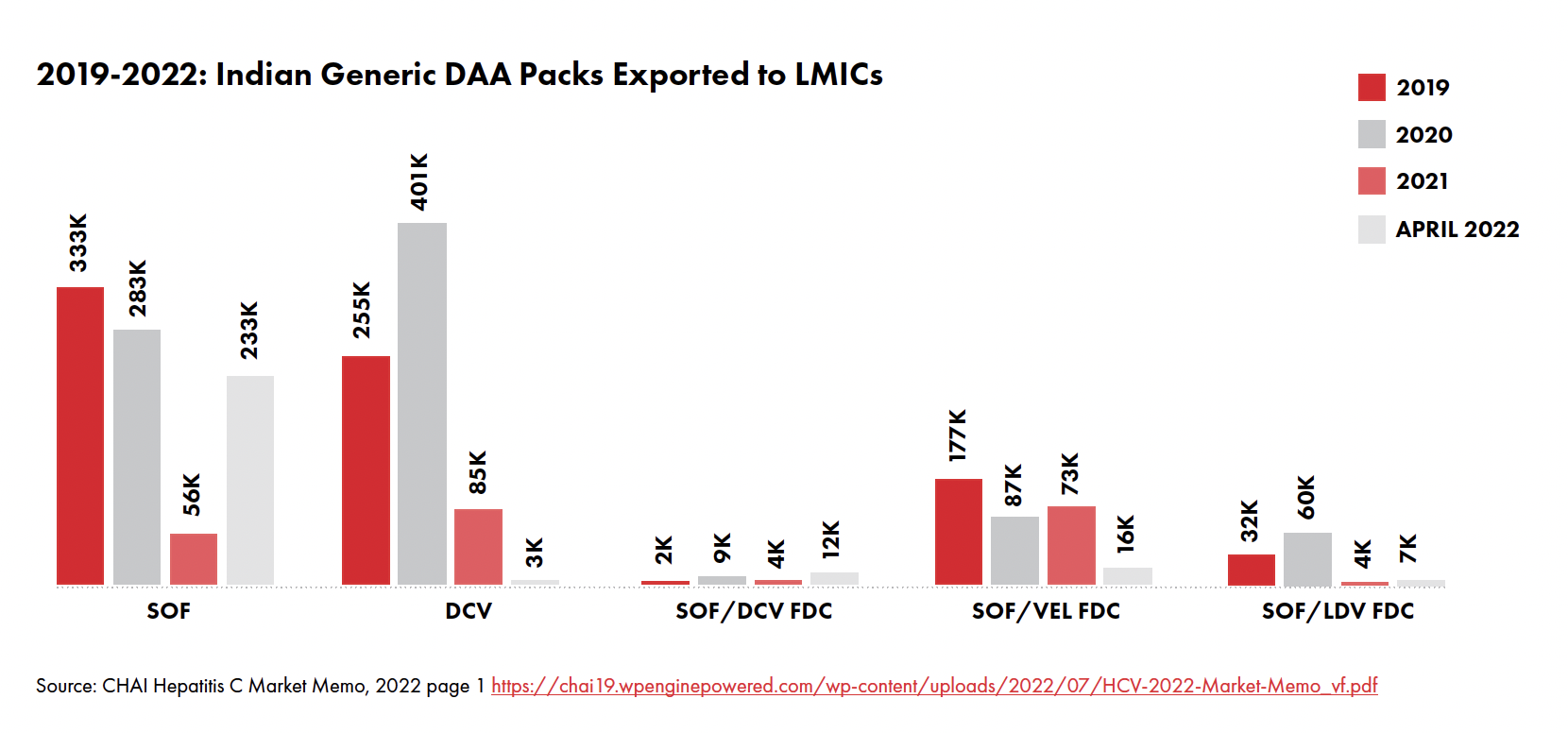

2. Low Demand for DAAs

Demand for DAAs across LMICs is very low due to a lack of political will and leadership to prioritize and invest in HCV elimination, and low awareness and uptake of HCV testing. There is minimal effort to raise awareness about HCV, to scale-up HCV services, or to streamline the complex HCV diagnostics pathway, often involving high costs, multiple clinic visits, and delays in treatment initiation following a positive diagnosis. As a result of these gaps, and the fact that people with chronic HCV may remain asymptomatic for up to two decades after infection, only one in five people with HCV actually know their status. This has been further compounded by the 2019 COVID-19 pandemic as health programs across the world shifted focus away from other health priorities to focus on health needs arising from the pandemic.

Some countries, however, such as Egypt and Malaysia, have shown political leadership resulting in robust measures to test and treat people with HCV to meet the 2030 viral hepatitis elimination goal. To increase demand for DAAs, health programs need to identify, fund, and implement measures to find and treat people with HCV. This includes public education about HCV; mass screening programs to find the missing millions of people living with HCV; and scaling up, simplifying, and decentralizing diagnostic services to enable early treatment initiation. Programs must implement test-and- treat programs to avoid loss to follow-up, and integrate HCV care into sexual and reproductive health programs, HIV programs, harm reduction and non-communicable diseases programs.

3. Treatment Restrictions

Various restrictions implemented by countries prevent people living with HCV from accessing treatment. Examples of restrictions include requiring people to be sober before they can access HCV treatment; limiting HCV care provision to specialists, as is the case in Cote d’Ivoire and Bangladesh; and a reluctance to launch mass HCV screening campaigns for fear of not being able to afford to treat all of those with confirmed viremic infection. While some of these measures may limit government spending on HCV in the short term, the long-term consequence on health programs is enormous. When treatment access is restricted, HCV transmission continues, and people who could have benefited from early cures develop complications like cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, and liver cancer, requiring more expensive (and sometimes unavailable) interventions like liver transplants, which cost more to health programs.

Investment cases for HCV elimination in Uganda, Cameroon, and Vietnam have demonstrated that HCV elimination is cost- effective and would save health systems enormous resources in the long-term. To ensure that everyone with HCV has access to the cure, national health programs need to eliminate all restrictions to HCV care as recommended by the WHO and scale up screening to find and treat everyone with HCV.

4. Non-Implementation of Updated WHO Recommendations on HCV Care

In 2022, to expand access to HCV care, WHO published the Updated Recommendations on the Treatment of Adolescents and Children with Chronic HCV Infection and the Updated Recommendations on Simplified Service Delivery and Diagnostics for Hepatitis C Infection, outlining three key measures countries need to implement to ensure integration and task sharing:

- HCV testing and treatment services should be provided at the same site through decentralization of care to lower-level

- HCV care should be integrated into other services like primary care, harm reduction programs, prison health programs, and HIV services.

- Countries should promote task sharing through delivery of HCV testing, care, and treatment by appropriately- trained nonspecialist doctors and

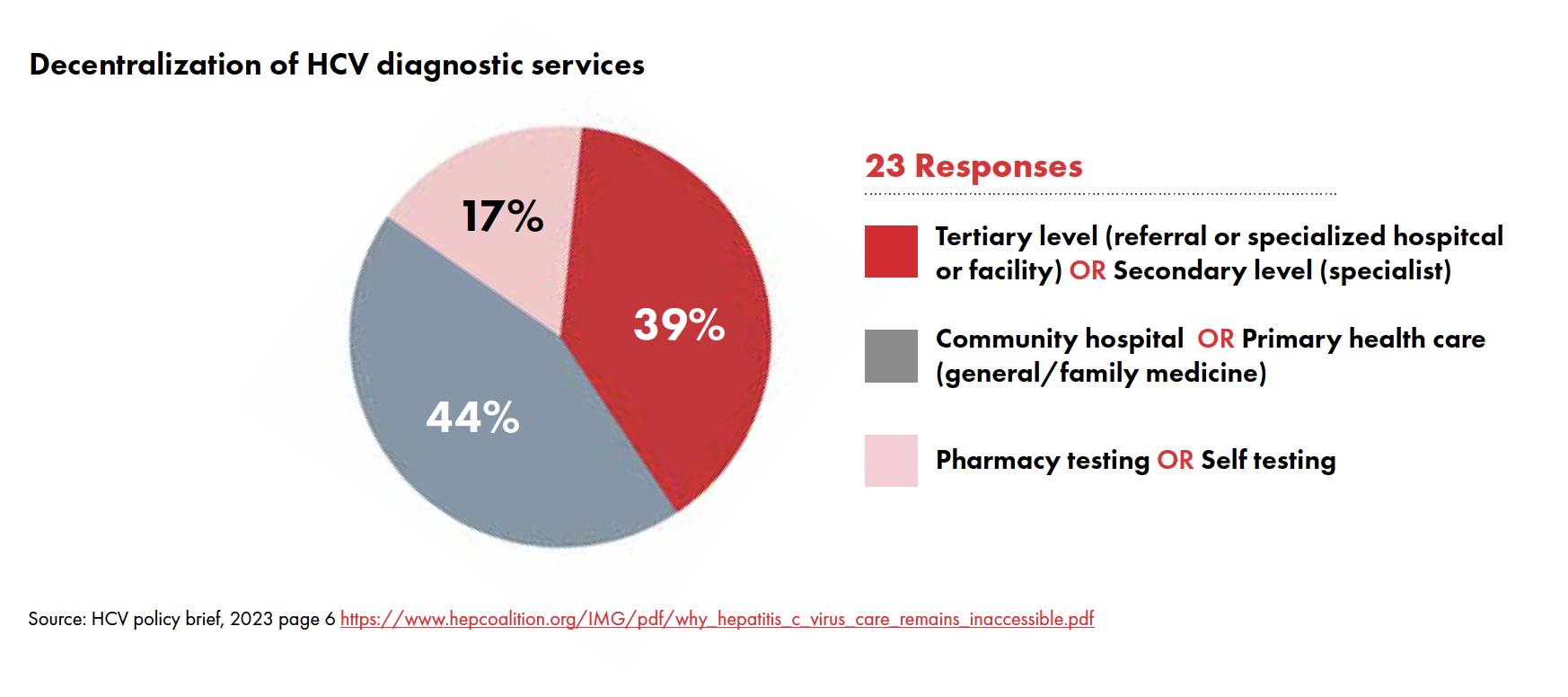

Following a survey of 23 countries earlier in 2023, TAG found that these guidelines have not been put into practice: HCV diagnostic services are still highly centralized with 39 percent of the countries surveyed offering these services only in tertiary or secondary levels of care (specialist/reference hospitals and clinics).2 Health programs must incorporate and implement WHO recommendations to ensure that HCV care is accessible to everyone.

5. General Neglect of HCV High-Burden Populations

HCV high-burden population groups include people who use and inject drugs (39.2%),3 men who have sex with men (3.4%),4 people in incarceration (15.1%),5 and people living with HIV (2.4%).6 Given that these population groups are marginalized instead of prioritized in national health strategies, these high-burden population groups may avoid health care facilities in fear of stigma, discrimination, and in some cases, police arrest. Health advocates need to work with their communities to raise community concerns and voices when engaging with policymakers and other stakeholders and to continue to push for evidence-based approaches to public health programming. Policymakers and health program implementers need to prioritize policies that address stigma and discrimination among high-burden key populations in HCV policy and health programs generally.

Endnotes

- WHO prequalification of medicines is a service provided by the WHO that involves an assessment of the quality, safety, and efficacy of medicinal products. WHO Prequalification gives international procurement agencies the choice of a wide range of quality medicines for bulk purchase for distribution in resource- limited countries.

- Treatment Action Group. Have a Heart, Save My Liver! Why the Hepatitis C cure remains inaccessible [Internet]. 2023 May (cited 2023 July 31);6. https://www.hepcoalition.org/IMG/pdf/why_hepatitis_c_virus_care_ pdf.

- Grebely J, Larney S, Peacock A, Colledge S, Leung J, Hickman M, et al. Global, regional, and country-level estimates of hepatitis C infection among people who have recently injected Addiction. 2019;114(1):150–66.

- Grebely J, Larney S, Peacock A, Colledge S, Leung J, Hickman M, Vickerman P, Blach S, Cunningham EB, Dumchev K, Lynskey M, Stone J, Trickey A, Razavi H, Mattick RP, Farrell M, Dore GJ, Degenhardt L. Prevalence and incidence of hepatitis C virus infection in men who have sex with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Jan;6(1):39–56.

- Dolan K, Wirtz AL, Moazen B, Ndeffo-Mbah M, Galvani A, Kinner SA, Courtney R, McKee M, Amon JJ, Maher L, Hellard M, Beyrer C, Altice FL. Global burden of HIV, viral hepatitis, and tuberculosis in prisoners and detainees. Lancet. 2016 Sept;388(10049):1089–102.

- Platt L, Easterbrook P, Gower E, McDonald B, Sabin K, McGowan C, Yanny I, Razavi H, Vickerman P. Prevalence and burden of HCV co-infection in people living with HIV: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infectious 2016 July;16(7):797–808.