The push for affordable HIV treatment doesn’t end with patent expirations

By Tim Horn

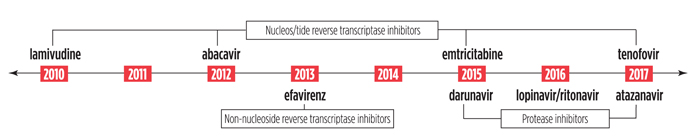

Expiry of guidelines-preferred and -alternative first-line ARTs

The United States is on course for some much-needed economic relief from the crippling cost of HIV treatment, with the anticipated arrival of generic versions of guidelines-preferred antiretrovirals. However, much preparation is required to maximize price competition, maintain patient choice, and ensure that savings are used to the advantage of people living with HIV.

With the patent expiration of efavirenz sometime this year, a generic-based regimen comparable to Atripla is on the horizon: efavirenz combined with lamivudine and branded tenofovir DF (Viread). According to recent mathematical modeling conducted by Rochelle Walensky of Harvard Medical School and colleagues, the U.S. health care system savings associated with this regimen could be up to $920 million in the first year alone.

The study has stirred up a much-needed dialogue on coming generics, but it has also come under criticism for its projection of reduced efficacy using efavirenz/lamivudine/Viread: a switch could shorten life expectancy by 4.4 months. This finding was based on two assumptions: 1) the increased pill burden would hinder adherence and reduce viral suppression, leading to worse outcomes, and 2) lamivudine is potentially inferior to emtricitabine and may increase the frequency of drug resistance, potentially affecting viral suppression efficacy in second-line therapy.

Lamivudine is, however, considered a safe and effective alternative to emtricitabine, according to a World Health Organization (WHO) analysis. WHO HIV treatment guidelines, released in 2010, also consider lamivudine in combination with efavirenz and tenofovir DF to be a preferred first-line regimen for adults and adolescents with HIV. Additionally, half-life and potency differences between lamivudine and emtricitabine are likely negated when either are combined with highly effective agents with long half-lives, notably efavirenz and tenofovir DF.

Limited data are available confirming that once-daily coformulations are associated with higher adherence rates compared with once-daily regimens involving two or more pills. According to a recent small cohort analysis, though participants taking once-daily regimens had higher adherence compared with participants taking twice-daily regimens, there was no difference among those taking Atripla compared with those taking once-daily regimens of multiple pills. Moreover, of the four preferred initial combination regimens for ARV-naïve HIV-infected adults and adolescents specified in the U.S. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-1-Infected Adults and Adolescents, two require three tablets once a day and one requires twice-daily dosing.

As single-tablet, once-daily regimens are highly desirable because of their convenience, preference among people with HIV and healthcare providers, and potential for lower out-of-pocket insurance copayments, the study and development or importation of U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved fixed-dose combination tablets will remain a priority as safe and effective agents come off patent over the next few years. Yet the immediate reality is the anticipated approval and availability of generic efavirenz; even if combined with the branded coformulation of tenofovir and emtricitabine (Truvada), savings in the U.S. were modeled by Walensky and colleagues to be $560 million in the first year alone.

For cost savings to occur, competition among generic manufacturers will be required. Walensky’s projections are based on 75% price reductions—an assumption based on competitive cost-cutting seen when non-HIV drugs become available generically. To achieve this, policies such as mandatory generic substitutions may increasingly become the norm.

Though it is only through market competition that drug pricing would no longer be determined only by what the market will bear but also by what it can sustain, activists need to ensure that patient and provider choice of treatment options is not unduly restricted as a result.

Lastly, we need to ensure that any savings are reinvested in HIV. With roughly one-third of people with HIV in regular care and only one in four being effectively treated, redirecting funds for testing, linkage-to-care, and retention efforts has never been needed more.•