By Bryn Gay & Annette Gaudino

Are we on track with WHO targets[1,2] to eliminate the hepatitis C virus (HCV) by 2030? Andrew Hill, Senior Research Fellow, Liverpool University unveils powerful research that compares 91 countries’ data on HCV prevalence, diagnosis, treatment, and income level. One central concern is that annually treating an estimated 1.42 million (2%)[3] people with diagnosed HCV infection—especially those with healthcare coverage—is insufficient given the enormity of the epidemic. We have yet to scale up screening, testing, and linkage to care for the estimated 56.8 million (80%)[4] with undiagnosed HCV infection. In addition, we must remove the worldwide stigma in treating and re-treating prisoners and people who use drugs, and lift treatment restrictions. Health departments also need to understand the actual costs of “test and cure,” which are decreasing in the face of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) competition. There’s no excuse not to commit to elimination.

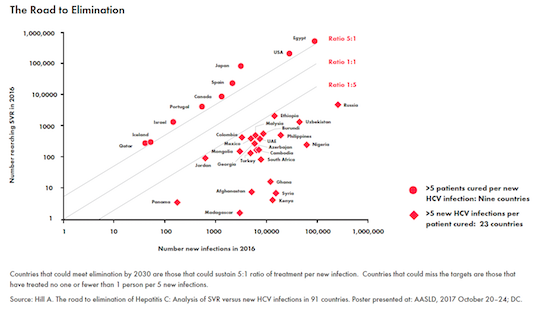

BG: Based on 2016 data, your research shows that 10 countries[5] have cured >5 patients for every new infection. Do trends suggest that these countries will eliminate HCV?

AH: We’re going to have to start treating far more people—at least 5 million people worldwide every year [vis-à-vis] the 1.5 million new infections occurring annually. In some countries 2016 was the best year, and after that, treatment rates seem to be falling. To eliminate HCV [countries must cure 5:1] consistently for another 12 years. Countries like Australia that have unlimited access to treatment for a fixed price, they might be able to sustain it. Countries like the U.S., where [it seems] mostly insured patients are treated,[6] they might not be able to manage it. If you’ve got people who have been recently infected by using intravenous drugs [they’re] a lot less likely to be insured. Even if they are covered, there might be [sobriety] restrictions at the state level. And even if they’ve been re-infected they might not be eligible for treatment for a second time. At the moment it’s just not looking like elimination is going to be possible because we are just not treating enough people.

BG: You’ve coined the term “diagnostic burnout” to describe the point when all diagnosed people with HCV have been treated and you have to find and diagnose new cases. What can countries do to avoid diagnostic burnout?

AH: There’s not enough people being diagnosed every year to keep up with the treatment rates, called “diagnostic burnout.” You’ll run out of people who are known to have HCV and who can get treated. Even among diagnosed people there are going to be some people who fall through the cracks, who live in states where they don’t have health insurance. Countries [or states] need to be given an estimate of what it would really cost to test and treat. In Egypt, a 12-week cure costs US$100, and all of the diagnostic tests cost US$25, so they have an all-in package of the cure for US$125. In the U.S., you could not even get one tablet of HCV treatment for US$125. Meanwhile in Egypt, 3 million people have already been cured, and there are plans to test 42 million people in the next three years. Other countries need to learn from Egypt and set up similar low-cost test and treat programs.

BG: How does patients’ treatment access compare across high-income countries, like the U.S., UK, or in Europe?

AH: [In the U.S.,] we’re already starting to reach a situation where there are just not enough diagnosed, insured people who are linked to care, who can get cured. In Australia, they’ve paid a fixed amount of money and they get unlimited treatment. It’s like “all you can treat”—like going into a restaurant and having unlimited access to the buffet. Last year they had a price for DAAs of US$8,000, which is way below any price that’s available in the U.S. or Europe. [It’s] a very interesting model for other countries, [to] pay a fixed price to a company and [get] unlimited access, called a “risk-sharing” deal.

BG: Many countries have struggled to collect accurate surveillance data on HCV. How confident should we be with the data tracking our progress?

AH: Worldwide we still [have] an epidemic of 70 million people. We don’t have the [same] accuracy [with HCV] estimates that we have in other diseases. Not enough samples have been done. If we look at the data we still don’t have this assurance that we’re on the right track. We have some countries where you’re getting 100 people newly infected for every person cured. I think we can be fairly sure that there’s a huge range of responses to HCV between countries. Egypt, Spain, Australia, and Portugal are doing really well; other countries in Eastern Europe and Africa haven’t really started to go on a path to eliminate HCV.

BG: What are immediate actions that countries lagging behind can take to accelerate progress toward elimination by 2030?

AH: Every country needs to start testing the people who are at the highest risk of hep C infection. For some countries that’s on par with having to go into prisons and testing all the prisoners, or reaching out to people who use intravenous drugs. They need to take the blame out of medicine. We can’t keep blaming people for having particular diseases; we just need to get on with it and cure them. Once those people are cured, you’ve really started to tackle the epidemic.

BG: What are the implications if we miss the WHO targets?

AH: What a missed opportunity that would be—you’ve got an infectious disease that kills hundreds of thousands of people a year, and can be cured for about US$50, and we’re not tackling it. How crazy is that?! It would just be such a classic case of great commercial success—companies making billions of dollars—but medically a failure. It would show that we just don’t have our priorities right—where the rich people in high-income countries get cured for vast amounts of money, and still there’s not enough left to treat the poor people who are in the most need?

AG: Trump has said Pharma is “getting away with murder” and claimed “the world is taking advantage of us.” Is he right? What are the reasons that other high-income countries pay significantly less than in the U.S. for the same medicines?

AH: The U.S. spends approximately US$300 billion per year on medicines across all therapeutic areas. The U.S. pays, on average, 2.5–3 times more for patented medicines than countries like Spain, UK, or France. The overspend for the U.S. versus the UK is [about] US$100 billion, which is a substantial proportion of the [US] Gross Domestic Product.

As part of US law, the main payers (Medicaid, Medicare) are not allowed to negotiate drug prices. If you look at the UK, we negotiate drug prices to justify the value of a medicine against its cost. [There are] similar systems across Europe, Australia, and Canada. The U.S. pays such a high amount of money because it doesn’t negotiate. The exception to that is Veterans Affairs, where they actually do negotiate and they have significantly lower prices. [With this overspent amount], you could wipe out HCV, you could treat everybody for HIV. But it’s not being done because of this ridiculous policy of not negotiating prices, which Donald Trump has actually done nothing about!

BG: Your other research highlights the significance of generic competition in dramatically reducing the cost of DAAs to a fraction of high-income country prices, even when a 10% profit margin is included. Has this increased people’s access to the cure and increased treatment starts?

AH: If a country gets behind a health campaign, great things are achievable. You have to have commitment at the highest level. That helps to get rid of some of the stigma. [There needs to be] more health campaigns to make sure [scale up] actually happens. Fundamentally, countries need to start making this more of a priority. [HCV] is very cheap to diagnose, very cheap to cure. Just add it into your current services with minimal extra costs.

BG: How can activists use this research and participate in policy-making decisions that see more people getting tested and treated?

AH: We need to start going to health departments and saying, “This is the size of the epidemic, and this is how much it could cost to treat and cure everybody.” [When policy makers] realize how cheap it is, they would become interested in it. People hear it’s US$84,000 for one treatment course, but it’s not that anymore. Even in the U.S. [the net price is] US$20,000 to US$25,000. Even if it’s US$100, and you’ve got 100,000 people, and you say, “It’s US$10 million,” for that you’ll have an epidemic that’s been eliminated. People are not going to get liver cancer, they’re not going to get liver cirrhosis, and most importantly, they’re not going to spread it to other people. There are huge benefits to countries for eliminating epidemics. The cost of treating people with liver cancer—you’ve got people in the highest productive time in their lives, dying from liver cirrhosis—it’s just unnecessary and it shouldn’t be happening.

References

- The WHO targets for elimination are to diagnose 90% of people infected with HCV, reduce mortality from existing levels by 65%, and treat 80% of infected people.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global report on access to hepatitis C treatment: Focus on overcoming barriers. Geneva: WHO; 2016. http://apps. who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/250625/1/WHO-HIV-2016.20-eng.pdf?ua=1

- Database of Polaris Observatory. [Internet]. Lafayette (CO): CDA Foundation, 2016 [cited 2018 February 25]. http://cdafound.org/polaris-hepC-dashboard/

- Ibid.

- Egypt, U.S., Australia, Japan, Spain, Canada, Portugal, Israel, Qatar, Iceland.

- 2016 Polaris data estimates 625,000 have been treated in the U.S.