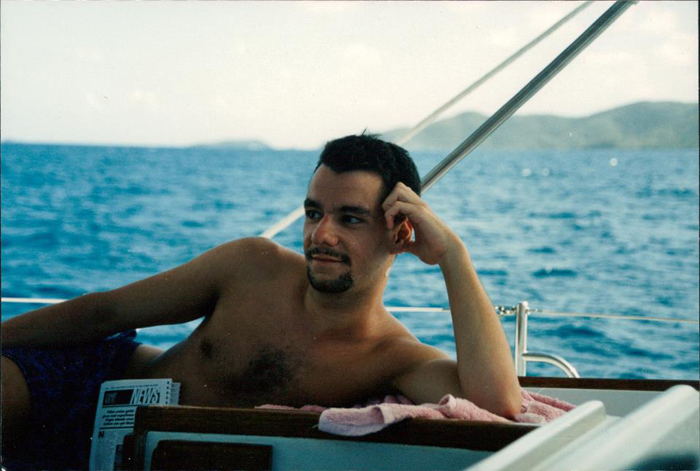

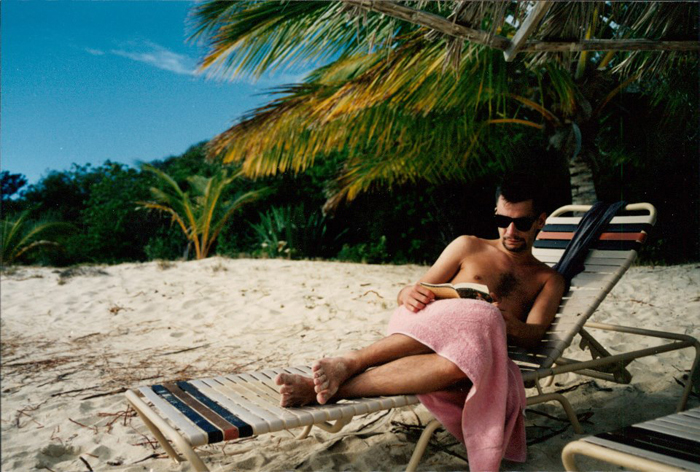

Patrick Spencer Cox

March 10 1968 – December 18 2012

December 18, 2012 – Today in New York, Spencer Cox died. He was one of the most brilliant of the first generation of AIDS treatment activists. He created the study design that led to full approval of ritonavir in 1996 using the optimized background regimen (such as it was in 1995—any available nucleoside analogue alone or in combination) with a randomization to ritonavir versus placebo on top; this has been the paradigmatic study design ever since.

In the six-month data from that study, those on ritonavir plus optimized background had 50% of the mortality of those on background alone. Ritonavir was approved on February 28, 1996; Merck’s rival protease inhibitor, indinavir, was approved the next day.

The U.S. and European/Australian/rich-world death rate from AIDS dropped by 70% in two years.

Fourteen million life years have been subsequently saved through this approach.

Unfortunately, Spencer himself did not benefit from these advances and indeed succumbed to a form of therapeutic nihilism and despair which led him to his untimely death early this morning from advanced AIDS and organ failure.

It’s as if President Ronald Reagan shot Spencer at 20 in 1988 and the bullet didn’t kill him fully until today.

Spencer died of despair, racism, homophobia, AIDS-phobia, and a host of other ills that afflict our country and our world.

He saved millions of lives, but could not save his own.

He will go down in history—but we wish he were still enriching our world today.

March 10, 1968–December 18, 2012

Patrick Spencer Cox, RIP.

We love and honor your work, life, legacy, and memory.

TAG Reports by Spencer Cox:

FDA Regulation of Anti-HIV Drugs: A Historical Perspective (August 1995)

Evaluation of AIDS drugs today does not just affect those who are currently ill; our planning now will determine the quality of HIV treatment for the next generation of people with HIV/AIDS. If we fail to address the basic question of efficacy standards now — “At what point in the development process do we reliably determine that a treatment can extend health and life?” — then our drug development systems, and our standards of HIV treatment are destined to leave us with substandard therapy for most HIV- infected persons, serious vulnerability to fraudulent claims, and ultimately, to unnecessary sickness and death.

We must and can do better. In continually reviewing and improving our regulatory mechanisms, it may be possible to reconcile the seemingly opposed needs for access to new therapies and reliable information about their efficacy.

The Antiviral Report: A Critical Review of New Antiretroviral Drugs & Treatment Strategies (June 1998)

In January, 1996, at the Third Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections in Washington, DC, I found myself standing amidst some very rude scientists with sharp elbows in a generic overcrowded conference hall, staring at the survival curves of patients treated with ritonavir in combination with nucleoside analogues, and I started crying. Over the course of the six month study, ritonavir-treated patients were surviving much more frequently than a similar group of participants who had been treated with a placebo and nucleoside analogues. AIDS research had finally paid off; effective therapy would be available for the hundreds of thousands of HIV-infected people in the United States, including some of those for whom I care most dearly.